Introduction

This research aims to empirically examine how solution-focused/problem-focused communication in the workplace influences the followership behavior of Japanese non-managers. The study of followership has been inadequate because it has received less attention than leadership research (Tanoff & Barlow, 2002). In recent years, followership has been given attention in different countries (Ehrhart & Klein, 2001) and research is slowly accumulating.

The flattening of organizations in Japan has increased the number of subordinates per manager. Managers are therefore able to allocate less time to their subordinates. Because managers are required to both perform field operations as a staff and manage as a manager. As a result, managers are less likely to have leadership opportunities (Nishinobo, 2021). Furthermore, the advancement of information technology has made society a place where subordinates can quickly obtain various information necessary for their work. The Japanese Cabinet Office (2018) reported that young people have a higher level of IT literacy. In other words, the younger the age, the more influence they can have through information. Against this background and due to societal changes, followers are stronger and leaders are weaker than before (Kellerman, 2012).

Thus, followership has been given attention from both practical and academic perspectives, and followership research is now gradually accumulating. However, Matsuyama & Mori (2022) pointed out that fewer studies have examined the independent variables of followership than those that have examined the outcome of followership. To develop followership theory in the future, research on the independent variables of followership will be necessary.

This research focuses on solution-focused/problem-focused communication as an independent variable of followership.

The solution-focused approach was developed in the 1980s as a form of psychotherapy (see for example Kitai & Shimada, 2022). Solution-focused approaches have been paid attention in various fields due to their effectiveness (Kitai et al., 2017). For example, the solution-focused approach has expanded practically to coaching. It has thus spread to the fields of psychology and business administration, where it is applied as solution-focused management. However, there is little empirical research on solution-focused management in the field of business administration. Lately, Kitai (2020) has developed a solution-focused/problem-focused communication measurement scale that is easy to use in the workplace and has reliability and validity. It is expected that this measurement scale will be refined in the future and that empirical research on solution management will accumulate in the field of business administration.

As discussed in more detail below, this research uses the solution-focused/problem-focused communication measurement scale of Kitai (2020) to conduct empirical research. Kitai (2020) confirms the reliability and validity of the solution-focused/problem-focused communication measurement scale. This research aims to contribute to the development of solution-focused management in the field of business administration. In addition, this research can also contribute to the development of followership research by clarifying the independent variables of followership empirically.

Literature review

Definition of Followership

Few followership studies have defined followership (Baker, 2007; Crossman & Crossman, 2011). Some researchers have defined followership, but as with the leadership definition, there is no unified view on the definition of followership (Nishinobo, 2021; Ono, 2013). However, most followership studies to date have defined followership as the influence or act of influence exerted by a follower (Matsuyama, 2016). For example, Crossman & Crossman (2011) defined it “as the opposite of leadership in a leadership/followership continuum, a direct or indirect influential activity, or as a role or a group noun for those influenced by a leader”. Looking at the definitions in Japan, followership is defined as “the exercise of influence by followers through support activities to leaders to achieve their objectives” (Shimomura & Kosaka, 2013) and “followers share organizational goals with leaders and act toward those goals to directly or indirectly influence the leader and the organization” (Nishinobo & Furuta, 2013). Fukuhara (2017) also explains that the premise for defining followership is that "followership is the process of influencing leaders by mobilizing informal authority, or power not attached to a position, such as expertise in performing a task, personal connections, and other resources.

This research would be based on the definition of Nishinobo & Furuta (2013). There are three reasons for this. The first reason is that this research takes the position of the influence paradigm. The second reason is that followership influences are perceived to be both direct and indirect. The third reason is that Nishinobo & Furuta’s (2013) definition of followership is based on interviews with people working in Japanese organizations.

Dimension of Followers

Kelley (1992) categorized followers according to the two dimensions of Independent, critical thinking, and active. Independent and critical thinkers in followers consider the impact of their actions. Followers who are dependent and uncritical tend to obey their leader’s orders. Active is the second dimension used to determine the sense of ownership that the follower demonstrates (Figure 1). Kelley used these two dimensions to classify followership into five types. Kelley emphasized that an exemplary follower is unique and recommended that one be an exemplary follower.

Kelley’s Model of Followership

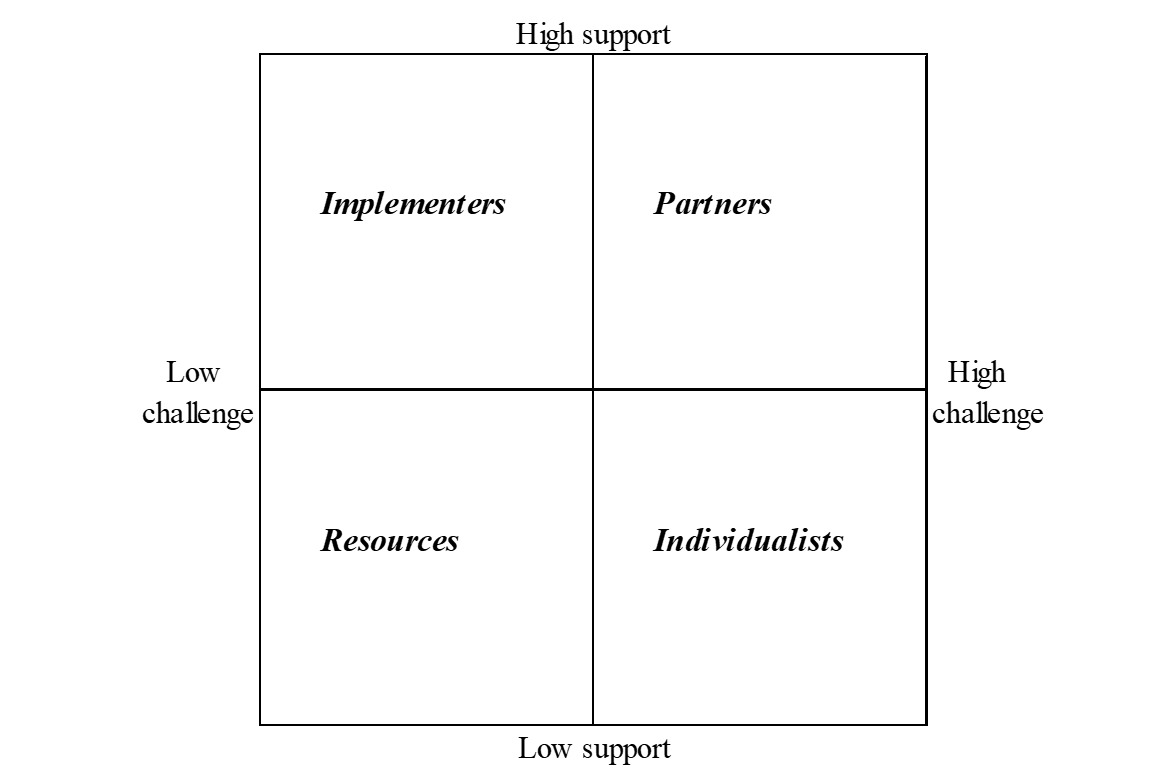

Next, Chaleff (1995) categorized followers according to the two dimensions of support and challenge (Figure 2). The support is the degree of support for their leader. The challenge is the degree to which followers are willing to challenge their leaders whose actions or policies undermine the goal of the organization. Chaleff considered followers who met these two dimensions to be courageous followers. He believed that courageous followers are unique and ideal followers.

Chaleff’s Model of Followership

Kelley (1992) and Chaleff (1995) conceptualized followers as having two dimensions and insisted that followers who act in these two dimensions are the unique ideal followers (Nishinobo, 2021). Nishinobo & Furuta (2013) conceptualized followers into three dimensions followership (active behavior), followership (critical behavior), and followership (considerate behavior) in Japan. Followership (active behavior) is demonstrating abilities for their leaders and the organization with challenging tasks. Followership (critical behavior) constructively criticizes their leaders and asserts their ideas when followers think leaders are wrong, based on follower’s ethical standards. Followership (considerate behavior) is to make their leaders look good. Nishinobo & Furuta (2013) suggested that followership (considerate behavior) is a unique dimension which is not found in the past research. On the other hand, followership (active behavior) and followership (critical behavior) are similar to the two dimensions of Kelley and Chaleff.

Independent Variable of Followership

Researchers have shown to have a positive influence as independent variables of followership so far are affective commitment (Nishinobo, 2014, 2015a, 2023), leadership (maintenance behavior) (Nishinobo, 2014, 2023), official position (Nishinobo, 2015a, 2022, 2023), years of nursing experience (Nishinobo, 2022), existence of key persons (Nishinobo, 2023), middle managers’ behavior (strict and rigorous management behavior, management behavior of trust and approval) ) (Persol Research and Consulting, 2019).

As reviewed above, there is less research on the independent variables of followership than the outcome of followership (Matsuyama et al., 2023; Matsuyama & Mori, 2022). Herdian et al. (2022) reviewed past research on independent variables and dependent variables of followership, and similar trends were found. Therefore, the accumulation of research on the independent variables of followership is required. Furthermore, as can be seen from the above review, there are no independent variables related to the workplace level in followership research.

Based on the above discussion, this research focuses on solution-focused/problem-focused communication, which is a workplace-level variable. That is why past research suggests that solution-focused/problem-focused communication may be an independent variable of followership. The details will be reviewed in the next chapter.

Solution-focused management

According to Aoki (2014), problem-focused focuses on the cause of a problem and thinking of ways to solve it. On the other hand, solution-focused focuses on the future when the problem is solved and is a way of dealing with the problem that focuses on their strengths, possibilities, and the ideal state. Thus, a workplace where the analysis of the causes of problems such as the former is frequently discussed is a workplace where problem-focused communication is often practiced. On the other hand, the latter workplaces, where people pursue their ideals and explore available resources without overlooking small opportunities that lead to solutions, can be said to be workplaces where solution-focused communication is well practiced.

There are many solution-focused approaches, but all have in common that they focus on the desired future and strengths rather than past problems and weaknesses (Kitai, 2020). Solution-focused management is the application of this solution-focused approach to business management. Solution-focused management is a practical management approach that focuses on the strengths and successes of an organization or individual (Kitai et al., 2017). As Kitai, Suzuki, Uenoyama, & Matsumoto (2017) point out, the effects of past research on solution-focused management have not been measured using a large sample size, and only successful cases have been reported. It is necessary to accumulate systematic research on solution-focused management in the future.

Kitai, Suzuki, Uenoyama, & Matsumoto (2017) researched an empirical study on whether solution-focused management promotes proactive behavior among 1,308 employees working at Japanese car dealerships. Proactive behavior is developing their work to benefit the organization voluntarily (Suzuki, 2011).

Kitai, Suzuki, Uenoyama, & Matsumoto (2017) examined an empirical study by setting “solution-focused management promotes proactive behavior (hypothesis 1)” and “solution-focused management promotes proactive behavior more strongly when interdependence is high (hypothesis 2)”. Kitai, Suzuki, Uenoyama, & Matsumoto (2017) analyzed interdependence separately into task interdependence and goal interdependence. Task interdependence is defined as “the degree to which members depend on each other to perform a given task effectively” (Van der Vegt et al., 2001), and goal interdependence is operationally defined as “the degree of interdependence in achieving a goal, that means the degree to which the goal is shared between members” (Suzuki, 2011). The results of the analysis showed that solution-focused management didn’t influence proactive behavior. Then hypothesis 1 wasn’t supported. Next, the interaction between goal interdependence and solution-focused communication had a positive effect on proactive behavior, and hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

However, several problems can be found in their study. First, the measurement scale of job crafting was used because there is no measurement scale for proactive behavior. Suzuki (2011), on whose basis the job crafting measurement scale was used, stated that the scale for measuring job crafting is also underdeveloped. Suzuki (2011) also stated the definitions of proactive behavior and job crafting are different. Furthermore, there were only four items of the solution-focused management measurement scale that were used for the analysis, with two items being used for each solution-focused/problem-focused communication questionnaire. The results determined a low reliability of the measurement scales, with problem-focused communication at 0.528. Therefore, valid and reliable measurement scales for solution-focused management should be used in future research.

Theory and Hypotheses

The Effect of Solution-Focused Approach on Followership

Proactive behavior is seen as one element of followership behavior. For example, Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe, & Carsten (2013) categorized followership behavior into nine elements, and one of them is proactive behavior. In addition, Matsuyama (2016) proposed that there are three dimensions of followership, they are “active loyal followership,” “proactive followership,” and “passive faithful followership,” with proactive behavior as one dimension. Although this research differs from the above studies in its definition and positioning of followership, there is no problem in considering proactive behavior as an aspect of followership. This is because proactive behavior is similar to the concept of followership (active behavior), which is the position of this research. Therefore, we considered there to be no obstacle to thinking of proactive behavior as a dimension of followership.

As discussed in the previous chapter, solution-focused management did not directly affect proactive behavior, but the interaction between goal interdependence and solution-focused communication had a positive impact on proactive behavior. The definition of followership in this research is “followers share organizational goals with leaders and act toward those goals to directly or indirectly influence the leader and the organization”. In other words, organizational goals are shared between leaders and followers, and a state of high goal dependence is assumed. The questionnaire on followership (active behavior) includes the item “Work hard over understanding the demands and goals of your leader,” meaning that follower influences their manager in a high goal interdependence state. In light of these arguments, we proposed the following:

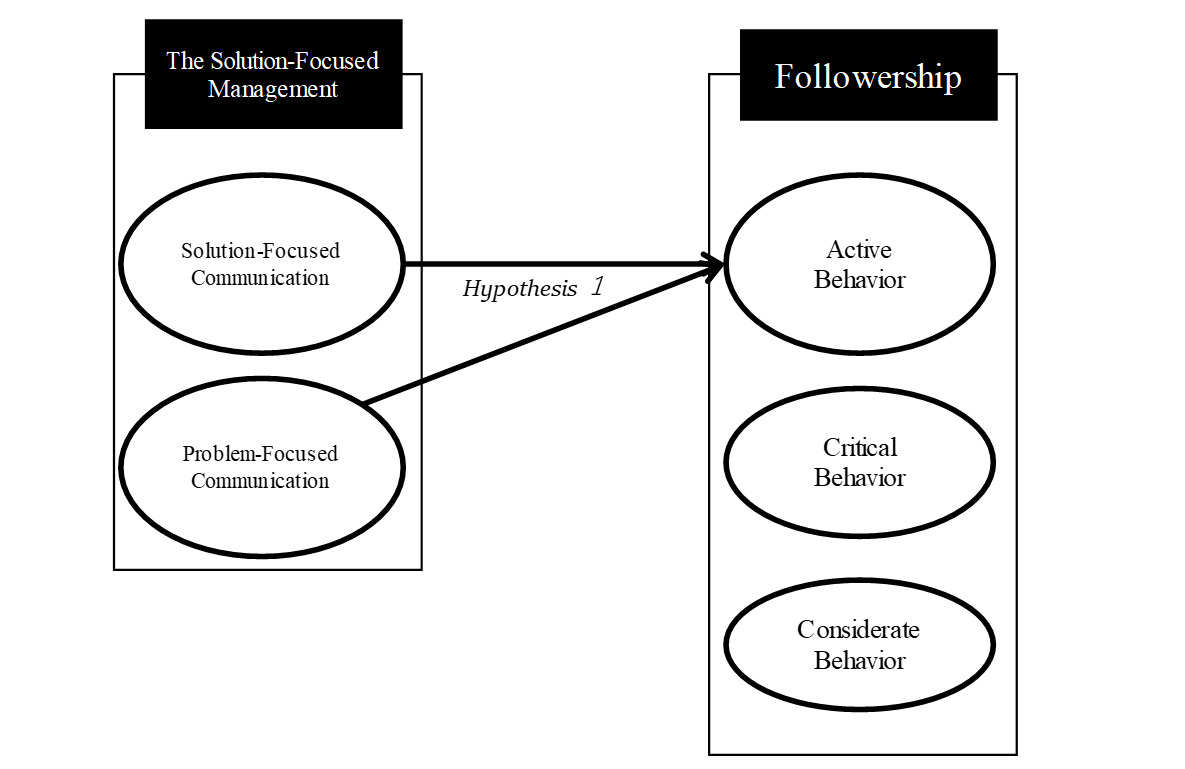

Hypothesis 1: Solution-focused management positively influences followership (active behavior).

From the above, the Hypotheses 1 model is shown in Figure 3.

So, does solution-focused communication or problem-focused communication have more influence on followership behavior? As mentioned in the literature review, Kitai, Suzuki, Uenoyama, & Matsumoto (2017) showed that only the interaction between goal interdependence and solution-focused communication had a positive effect on proactive behavior, and Kitai (2020) showed that solution-focused communication had a stronger influence on work engagement than problem-focused communication. Work engagement can improve employee performance, reduce turnover intentions, and increase organizational commitment (Tagoo, 2019). In addition, Kitai and Shimada (2022) showed that solution-focused communication was more strongly correlated with positive affect and self-efficacy than problem-focused communication.

Based on these research results, it seems that solution-focused communication promotes followers’ proactive behavior toward their leader more than problem-focused communication. we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 2: Solution-focused communication positively influences followership (active behavior) than problem-focused communication.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We surveyed 300 full-time employees from Japanese organizations using diverse industries to participate in this research through an Internet survey company. However, we excluded some answers because inappropriate responses were included (i.e., answering “1” to all questions, answering years of service are longer than age, and answering that respondents were in a managerial position and their leader was in a non-managerial position). We wanted to examine the followership behavior of Japanese followers toward their managers, so we selected the respondent who was in a non-managerial position and had a manager in a managerial position. Thus, the final analysis included 273 responses. The survey was conducted on February 22, 2023. The web survey screen provided explanations about ethical considerations and guarantees of anonymity, and consent for participation in the survey was confirmed.

Measures

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the solution-focused management and followership scales used in this research to identify their factor structures. Next, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to confirm that the questionnaire items of each scale captured the concepts we wanted to measure as expected. The principal axis factoring method (promax rotation) was used for the exploratory factor analysis. The reason for using promax rotation is that past research has shown a correlation between factors within solution-focused management and also within followership. Next, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses. Now, I will explain about the scales.

Affective commitment. The purpose of this research was to empirically clarify the effects of solution-focused management on followership behavior. Past research in Japan has shown that affective commitment has a particularly strong influence on followership behavior among the independent variables of followership behavior. To achieve the research objectives, we decided to use affective commitment as a control variable because it has the potential to strongly influence the objective variable, followership behavior. This is because multiple regression analysis removes the influence of a third variable that may affect the objective variable.

We used Kitai’s (2014) measurement scale for affective commitment. This measurement scale is a simplified version based on the Allen & Meyer (1996) measurement scale. A 5-point scale of responses (from 1 = I don’t think so at all to 5 = I think so very much) was used against the 3 question items.

Solution-focused management. We used the solution-focused management measurement scale developed by Kitai (2020). Kitai (2020) developed a reliable and valid instrument to measure solution-focused/problem-focused communication that can be easily used in the workplace. After reviewing past research, Kitai (2020) explained the reason why the measure of solution-focused management consists of solution-focused and problem-focused communication as follows. First, problem-focused communication is not necessarily the opposite of solution-focused communication. This is because the fact that solution-focused communication is not taken does not mean that problem-focused communication is active. Second, as past research has shown, problem-focused communication is not necessarily ineffective in solving problems. Third, problem-focused communication may solve problems in organizations where solution-focused communication does not take place. Fourth, there may be issues that have not been identified in previous research that make problem-focused communication more appropriate in organizations than solution-focused communication. Thus, Kitai (2020) pointed out the problem that the solution-focused communication scale has focused only on solution-focused communication as a common point. Furthermore, as Aoki (2014) points out, one of the strengths of Japanese companies is their ability to conduct “problem occur → investigate causes → improvement of problems.” In this way, there is a cultural background that has excelled in the problem-focused approach in Japan. Therefore, we believe that examining the effectiveness of solution-focused management with solution-focused/problem-focused communication as a component in the workplace of Japanese companies with this cultural background will contribute to the future development of solution-focused management research. Based on the above discussion, we use Kitai’s (2020) solution-focused management scale, which can measure both solution-focused and problem-focused communication, to achieve the purpose of this research.

Next, the latest version of the scale is Kitai & Shimada’s (2022), but it was not available at the time we requested it from the internet survey company, so we used Kitai’s (2020) scale, which was the latest version at the time. Kitai & Shimada (2022) modified some questionable items of Kitai’s (2020) measurement scale. A 5-point scale of responses (from 1: not at all agree to 5: completely agree) consisted of a total of 14 items with seven items each for solution-focused communication and problem-focused communication.

Followership. We used the Persol Research and Consulting’s (2019) measurement scale of followership. This scale is based on Nishinobo (2015 b) with modifications. Nishinobo’s (2015b) measurement scale had 53 items, and some of the questions were difficult for business persons to answer. The measurement scale revised by Persol Research and Consulting (2019) overcame these problems and simplified them. Parsol Research and Consulting (2019) conducted a questionnaire survey (N = 2,000) of business persons using this measurement scale. After analysis, the reliability of the scale showed sufficient internal consistency with followership (active behavior) (α =. 913), followership (critical behavior) (α =. 834), and followership (considerate behavior) (α =. 824). That’s why we use this scale in this research. The items of followership are 25 total including 12 items of followership (active behavior), 7 items of followership (critical behavior), and 6 items of followership (considerate behavior). A 5-point scale of responses (from 1: never to 5: always) was used against the 25 question items.

Results

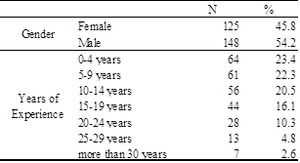

The average age of the participants was 36.04 years (SD = 8.2). In terms of gender, there were 148 men (54.2%) and 125 women (45.8%), with 0 to 4 years of service, 61 (22.3%) with 5 to 9 years, 56 (20.5%) with 10 to 14 years, 44 (16.1%) with 15 to 19 years, 28 (10.3%) with 20 to 24 years, 13 (4.8%) with 25 to 29 years, and 7 (2.6%) with 30 years or more (Table 1).

We first checked the ceiling and floor effects for all the questions and found no problems. Next, an exploratory factor analysis (principal factor method) was conducted on a measure of solution-focused management. After an exploratory factor analysis, two factors were extracted with an eigenvalue greater than 1. Since the factor structure was as clear as a priori dimension, we named the first factor “solution-focused communication” and the second factor "problem-focused communication " as in a priori dimension.

Then, an exploratory factor analysis (principal factor method) was conducted in the same way for the followership measurement scale. After an exploratory factor analysis, three factors were extracted with an eigenvalue greater than 1. Since the factor structure was as clear as a priori dimension, we named the first factor “followership (active behavior)”, the second factor “followership (critical behavior)” and the third factor" followership (considerate behavior)" as in a priori dimension.

Based on the results of the exploratory factor analysis, the number of factors for solution-focused management and followership were set to 2 and 3, respectively, to determine their level of fit. The indices used were the comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit (AGFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC).

Solution-focused management was CFI=.923, GFI=.878, AGFI=.831, RMSEA=.086, AIC=228.0, and followership was CFI=.897, GFI=. 822, AGFI=.788, RMSEA=.076, AIC=803.6. Thus, we judged the goodness of fit was within the acceptable range.

Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation, correlation coefficient, and reliability coefficient for each variable used in this research. We measured the reliability of the scale based on the two-factor model of solution-focused management and the three-factor model of followership. The result determined sufficient reliability of the scale, with affective commitment (α=.77), solution-focused communication (α=.91), problem-focused communication (α=.85), followership (active behavior) (α=.93), followership (critical behavior) (α=.89) and followership (considerate behavior) (α=.87). Thus, we considered that each measurement scale ensured a certain degree of internal consistency. Therefore, the high validity and reliability of our measure of followership is a contribution to the research of followership.

Then, we decided to use the mean value of the items comprising each factor as the variable score for subsequent analyses.

The reliability coefficient results also confirm that the measurement scale for solution-focused management developed by Kitai (2020) is sufficiently reliable in this research.

Finally, we used multiple regression to test our hypothesis 1 (see Table 3). The results of the analysis showed that solution-focused/problem-focused communication, or solution-focused management, had a positive influence on followership (active behavior). Therefore, the Hypothesis 1 was supported. In addition, solution-focused management influences all dimensions of followership. Thus, solution-focused management was shown to be an independent variable of followership. We also confirmed that collinearity was ruled out, as the VIF values were under 2.304.

Looking at Table 3, it can be seen that solution-focused communication had a stronger influence on followership (active behavior) than problem-focused communication. Therefore, the Hypothesis 2 was supported. In addition, Similar results were shown for followership (considerate behavior). To put it differently, solution-focused communication may have a greater influence on followership behavior than problem-focused communication. According to Kitai (2020), solution-focused has generally been shown in past research to be more effective than problem-focused in solving problems at the individual level. Therefore, it can be said that the results of this research were almost consistent with past research.

The results of this research indicated that followership is the outcome variable of solution-focused management. We also demonstrated empirically that solution-focused management, a workplace-level variable, is a factor that is an independent variable of followership. The significance of this research is that we were able to contribute to the development of both solution-focused management and followership research.

Discussion

We focused on the followership behavior of Japanese non-managers working in Japanese organizations in this research. Hypothesis 1 was to examine how solution-focused management influences followership behavior Results of our analysis revealed the following two points. First, solution-focused management has a positive effect on every dimension of followership behavior. Second, Solution-focused communication had a stronger influence on followership (active behavior) and followership (considerate behavior) than problem-focused communication. These results are discussed below.

Discussion of Study

Solution-focused communication promotes positive emotions and suppresses negative emotions by finding solutions to problems. It also enhances self-efficacy in problem solving. Furthermore, solution-focused communication has the effect of promoting further solution-focused communication statements (Kitai et al., 2017). Many followers have high levels of positive emotions and problem-solving self-efficacy in workplaces where are taken solution-focused communication. As a result, followers may be more likely to take positive action. According to Kitai, Suzuki, Uenoyama, & Matsumoto (2017), the interaction between goal interdependence and solution-focused communication had a positive influence on proactive behavior. And solution-focused management had a positive effect on followership in this research.

We examined only the influence on followership (active behavior) with hypothesis 1, but solution-focused management had a positive effect on every dimension of followership behavior. One possible reason for this is the strong correlation between the factors of followership behavior (see Table 2). In addition, according to the definition of followership, followership is the action taken by followers to share organizational goals with leaders and achieve organizational goals. We can think followers who have increased their work engagement and organizational commitment through solution-focused management may take critical actions toward their leaders in order to improve their work, or they may take considerate actions that put the leader in good stead. Through this research, we found that solution-focused management promotes followership behavior and may lead to improved organizational and individual outcomes.

We considered with hypothesis 2 that solution-focused communication had a stronger positive influence on followership (active behavior) than problem-focused communication, and although hypothesis 2 was supported, the results were similar for followership (considerate behavior). Conversely, there was no difference in followership (critical behavior). We suspect that the reason is due to the characteristics of problem-focused communication. Problem-focused communication focuses on the cause of the problem (Kitai, 2020), so it becomes a workplace that points out the problems and shortcomings of members (Kitai et al., 2017). In other words, in problem-focused communication, followers tend to take critical behavior not only toward members but also toward their leaders.

This research contributes to followership research by revealing that the independent variable of solution-focused management, which is related to the workplace level, influences followership behavior.

Practical Imprecations

The practical implications of the above research results are two points. First, each department should attempt to share the organizational goals it has permeated with all organizational members. Second, organizational development based on solution-focused management should be implemented. The content of communication in the workplace is intended to develop an organization that prioritizes solution-focused communication over problem-focused communication. When developing an organization, companies should make an effort to ensure that it is used in the context of daily organizational practice, rather than in the context of the organization such as 1on1. These are expected to elicit more followership behavior.

Limitations and Future Directions

The limitations and future research direction of this research are described in four points.

First, there are some biases in the collected data. The type of employment is limited to full-time employees, and only business people (non-managerial positions) are surveyed. For this reason, the results of this research cannot be immediately applied to the Japanese workforce as a whole. In the future, it will be necessary to collect data from a sample that includes a wide range of job titles and non-full-time employees.

Second, this research analyzed the results of the followers’ responses. Future research should examine the followership behavior of followers as seen by their leader.

Third, we can’t determine how goal sharing should be done. For example, it is impossible to determine whether it is more effective to share goals in a concrete or abstract way, or whether it is more effective to share both simultaneously. Future research will also need to be conducted on the methods and frequency of goal sharing by leaders.

Fourth, the measure of followership used in this study includes characteristics specific to Japan. Therefore, caution should be exercised when using this scale in organizations other than Japan.