The purpose of this article is twofold. First, to describe the development and design of a practical tool that helps to streamline the interventions that professionals can use in facilitating change in and between (human) systems in all possible intervention domains and thus transcends the domain of psychotherapy. Ergo, solution-focused applied psychology. Second, we want to provide a scientific foundation and validation of the solution focused practice by using Design Science Research methodology.

To our knowledge, this is the first application within the field of applied psychology of the DSR methodology derived from the engineering sciences. We have demonstrated that using that methodology, a professional practice (SoFAP) can be systematically validated. We did so by distilling points of interest, lessons learned, and best and bad practices from interviews with practitioners and comparative case analyses that then formed the building blocks of a robust protocol design that was subsequently tested in practice and improved accordingly.

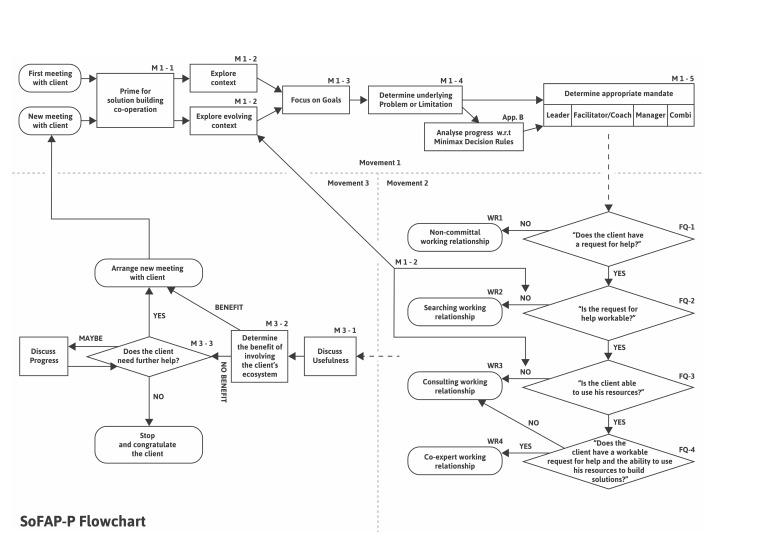

The result is a tool in the form of a differentiated flowchart that enables practitioners from all fields of applied psychology to refine and hone their solution-focused skills. The DSR methodology ensures that practitioners can stand their ground in professional as well as scientific discussions.

The Solution-Focused approach

The American psychiatrist and psychotherapist Dr. Milton Erickson (1901-1980) is known to have said: Each person is a unique individual. Hence, psychotherapy should be formulated to meet the uniqueness of the individual’s needs, rather than tailoring the person to fit the Procrustean bed of a hypothetical theory of human behavior, (Zeig & Geary, 2000).

His approach to applied psychology resonated with many practitioners who at the time felt that their field had become over-theorized. Indeed, ever since the emergence of psychology as a science in the late nineteenth century, the quest has been for a comprehensive theory about the functioning of the human mind and ways to influence it. Such a theory thus far however has not been found and all theories that have arisen with such an aim have their flaws and deficiencies.

In line with Erickson’s dictum, practitioners knew that these flaws are fundamental to and characteristic of any such theory and that therefore they cannot be overcome through revision and making theoretical adjustments. They felt that psychological theories or models reduce the complexity of the subject studied or limit their applicability to an increasingly narrow spectrum of psychological phenomena. In practice, this could lead to a situation in which a client is consistently misdiagnosed to suit the theory.

Looking for an alternative to traditional, problem-oriented therapy, this group of practitioners remained to a certain extent without direction. Erickson had given them inspiration, but his practice was too intuitive to serve as an example.

That changed in 1978 when Steve de Shazer (1940-2005) and Insoo Kim Berg (1934-2007) founded the Brief Family Therapy in Milwaukee, USA. Here they sought to transform Erickson’s intuitive approach to therapy into a more communicable method.

From the beginning, the aim was to minimalize the time patients suffer from their problems and to move as quickly as possible to better times. As their working hypothesis they assumed that patients always experience moments when their problems are different, less or even temporarily absent. This concept of ‘exceptions to the problems’ provided the basis for their philosophical stance that problems belong to a different logical class than solutions. This insight gave rise to the concept of solution-focused psychology.

Although the field of solution-focused psychology has significantly evolved since the 1970s, its root characteristics have remained largely unchanged. We will characterize the solution-focused approach by the axioms that support its practice:

-

Every human being and every human system is fully equipped to cope with life

-

Human systems (individuals, families, teams, companies etc.) always have resources at their disposal that they can use to reach their goals.

-

However dire the situation may seem, there are always practices that are worthwhile to keep doing.

-

There are always practices and behaviours that still work positively in spite of the problem.

-

Change works best on a foundation of what works well.

From these assumptions the solution-focused approach was developed.

Through the publishing of books such as Patterns of Brief Family Therapy: An Ecosystemic Approach (1982), Keys to Solution in Brief Therapy (1985), Clues: Investigating Solutions in Brief Therapy (De Shazer, 1988) and Putting Difference to Work (Frank & Frank, 1991), de Shazer popularized the solution-focused approach which rapidly spread throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The pioneering contributions of Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg as thinkers and clinicians initiated a paradigm shift in the field of psychotherapy and coaching that to this day is the primary reference upon which the extensive solution-focused literature and professional community bases its work. To honor their extraordinary importance, this article focuses on their pioneering work and develops it further in terms of scientific foundation and protocol.

Yet there is an ocean of interesting contributions and contributors available. An important overview of that ocean can be found on the European Brief Therapy Association website (Ebta.eu) with a convenient and easily accessible list of most peer reviewed articles (https://www.ebta.eu/sf-research-list/). And of course, based on de Shazer’s paradigm shift, professionals from various fields continue to expand their practice. One thinks of BRIEF London’s Best Hopes approach, the description building method, micro-analysis, etc., among others.

In the ocean of solution-focused literature being published, we want to highlight some attempts to establish protocols to facilitate the use of the solution-focused approach. These include Steve de Shazer’s original flowchart (complainant, visitor, client) and the successively improved flowchart designed by the Bruges Group (Korzybski Institute of which Cauffman was a founding member).

The tool we present here is a further improvement because it is -explicitly- a nonlinear, discursive, and iterative guide that takes into account the context, dynamics and requirements of each specific situation.

Design Science Research

In The Sciences of the Artificial ((Simon, 1969) Nobel Prize laureate Herbert Simon explores the fundamental differences between the natural sciences and the sciences of the humanities. He suggests a ‘science of design’ that is not limited to the physical or technological domain, but also encompasses the social field. It is his thinking that has inspired the construction of Design Science Research.

Based on Simon’s idea, Van Aken (2004) and later Denyer et al. (2008) undertake the challenge to formulate the defining characteristics of this ‘design science’, contrasting it specifically with the ‘explanatory sciences’. Summarizing their results, we may characterize the former as follows:

-

DSR is conducted from the perspective of an involved actor.

-

DSR is driven by an interest in field problems encountered by the actor;

-

DSR aims for the production of prescriptive knowledge (e.g. a protocol, a set of interventions) to solve the field problems concerned; hence design science is more focused on knowledge-to-improve than on knowledge-to-explain.

-

DSR justifies its research products largely on the grounds of pragmatic validity.

In this context, the research product containing prescriptive knowledge to solve field problems is referred to as the design. This is in accordance with Simon’s frequently quoted statement: Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones, (Simon, 1969). As the above characterization makes clear, DSR offers a discipline-independent paradigm of conducting scientific research.

As our research takes place in the field of applied psychology, this article will constitute an abstract design that can be individually customized. The individuals that benefit from our design are practitioners working in the domain of solution-focused psychology. In this introduction it only remains to explain how they will benefit exactly.

The field problem and the design objective

Because of its aversion to theorized problem-analysis, the solution-focused approach has in certain circles gained the reputation of being unscientific – a judgement that mostly roots in prejudice and disregards its extended literature.

After Berg and De Shazer had identified the two keystones of the solution-focused approach – differentiation in problem perception and future orientation – they developed specific interventions to prime their clients towards these two concepts. A variety of ‘scaling questions’ and the use of the ‘miracle question’ became the two major icons of the solution-focused approach. Disregarding the depth of the epistemological ‘thinking-behind-the-thinking’ that grounds the solution-focused approach, has led some psychologists and academics to -wrongly- view the solution-focused method as a superficial bag of tricks.

Despite the outcome research that makes the solution-focused approach an evidence-based model and because of its heavy focus on technical interventions, solution-focused practitioners, when debating with their problem-focused colleagues, often struggle to communicate the relevance and results of their way of working. Therefore, the choice in this article is made to define as field problem the relative lack of validation of solution-focused psychology approaches. Given the breadth of such a study, the field problem is specified in the following way:

Solution-focused practitioners themselves experience or

receive as criticism

that their way of working is not sufficiently validated.

To eliminate this field problem, it will suffice to design a validated protocol that fits within the solution-focused paradigm and that solution-focused practitioners can use to guide the interaction with their clients. As an extra condition it is stressed that the protocol is highly sensitive to the environment of the client (his or her material and immaterial context) to avoid the Procrustean trap discussed in Section 1.1 and to maintain a broad and realistic view on the challenges the clients face in real life. This led to the following formulation of a design objective:

To provide a validated and tested

solution-focused applied psychology protocol

to help clients in a productive way

to address their challenges.

The protocol should consider the client’s actual context

from the start.

From now on, we will refer to the solution-focused applied psychology protocol as SoFAP-P. In the next part we will describe the general tools offered by DSR methodology to design such a protocol and discuss some additional conditions. Then we will show how this applies to the case of our field problem in solution-focused psychology. Subsequently we present the actual design of SoFAP-P, whose validity is discussed in the last part of the article using evaluation techniques developed in DSR.

The practical and methodological aspects discussed in this article are described in detail in the twin books. ‘Creating Sustainable Results with Solution-Focused Applied Psychology, A Practical Guide for Coaches and Change Facilitators’ DOI: 10.4324/9781003320104 (Cauffman L., Routledge 2023) provides a guide for professional practitioners. ‘Solution-Focused Applied Psychology, A Design Science Research-Based Protocol’ DOI: 10.4324/9781003404477 (Cauffman L., Weggeman M., Routledge 2023) describes the methodological design process and is the first application of DSR in applied psychology. In this book, a dynamic version of the flowchart tool can be downloaded via a QR code (that one can also find infra in this article).

Designing the SoFAP-Protocol

The DSR methodology is widely used in a wide range of - mainly technical - application areas, from information systems on medical drug development to architecture, machine design, etc. Recently, much research (including doctoral research) has been conducted using DSR methodology, and as a result, that methodology has continued to evolve. We consider DSR mature enough to apply that methodology responsibly. This study is the first article to describe the use of DSR in psychology, and more specifically in solution-focused applied psychology. It therefore contributes to the emergence of an increasingly mature DSR methodology.

Preliminary design conditions

As mentioned in the introduction, the outcome of our research – the envisioned SoFAP-P – needs to be relevant from the perspective of an involved actor, i.e. a solution-focused practitioner. To guard the intended design against a lack of significance, we would do well to keep these four conditions in mind during its construction (Van Aken & Andriessen, 2011):

-

Practical relevance: The design should be relevant for everyday practice in the field. Too much reduction in the number of variables considered, or a too high conceptual level might risk the practical relevance for real-life use of the design.

-

Operational relevance: Professionals must be able to actually apply the design in their practice. To this end, the design presented must be consistent with the way practitioners are used to operate (face validity), and they must be able to quickly become familiar with the recommended design.

-

Non-obviousness: This condition refers to the degree to which the theory behind the design exceeds or complements the commonsense theory already in use. Furthermore, any contribution to existing practice should be non-obvious, for if the design is seen as a recurrence of commonly known knowledge, it is less likely to be adopted by practitioners.

-

Appropriateness: The design should be up-to-date and relevant to contemporary real-life problems in the field.

Some of these conditions already indicate that the design needs to be (implicitly) derived from literature, empirics and evaluated experiences of involved actor(s).

In the next section it is shown how the information required through this research was classified and instrumentalized.

The architecture of the design

As said before, DSR aims to combine theoretical knowledge and field understandings into an approach that can be used by practitioners. Knowledge-to-explain is used to develop knowledge-to-improve by scientifically analyzing practical, real-life field challenges and processes. Much of this knowledge is shaped in so-called design principles and design propositions.

Design Principles

For the sake of organization, it is common to distinguish between different kinds of design principles as derived from the research activities described above.

A review of relevant literature for example will generally lead to the identification of a number of Points of Attention, Limitations and Lessons Learned. From page 8 we will discuss these in generalized form, taking the liberty to transform all limitations into resource- and future-oriented points of attention. Networking experience on the other hand will allow for some Best Practices and Bad Practices to be formulated.

Design Propositions

In the introduction it was already stated that the design, once delivered, will need to be of a level of abstraction that allows it to be used by all individuals working in the field at hand. This is only possible under the assumption that social systems show comparable patterns that can be studied, as DSR indeed assumes. These patterns do not have causality as in clockwork systems, (Boulding, 1956) but they demonstrate sufficient causal potential to take them into account (Pawson & Tilly, 1997).

This view is at the basis of the so-called CIMO-logic that has been developed within the DSR framework. CIMO is short for Context Intervention Mechanism Outcome and consists of a brief description of a particular situation containing the answers to these four questions (Denyer et al., 2008):

-

What is the (field) problem? (Context)

-

Which action(s) should be taken? (Intervention)

-

How do the proposed actions lead to the desired effect? (Mechanism)

-

What result can be expected from the action? (Outcome)

Formulating such CIMOs yields design propositions.

In DSR, CIMOs are usually extracted from case studies. Of course, extracting a CIMO from a single case will result in a CIMO with a very specific context. This can be avoided by evaluating resembling interventions in dissimilar cases and identifying the similarities in the underlying mechanisms in order to construct a more general CIMO.

Testing the construction of the SoFAP-P design

In the context of constructive evaluation, two methods developed in DSR are of particular interest: α- and β-testing.

The purpose of an α-test is to present a draft version of the design to experienced practitioners and receive feedback regarding internal consistency, reliability, validity and usability in order to assess the extent to which the design meets the requirements. The design is theoretically tested by means of interviews, panel discussions, simulation based conversations, surveys and the like.

Following McKenney & Revees (2012), an α-test comprises ‘early assessment of design ideas’ by experienced actors. By means of interviews, panel discussions, simulation based conversations, surveys, etc., an α-test tests the nascent design for soundness and feasibility:

-

Soundness: Testing the propositions and principles that underpin the design and how these are operationalised in the design. Soundness also concerns the logical coherence of the design.

-

Feasibility: Conceptual testing of the design for feasibility in practice, answering questions as: To what extent can the design be used and applied in practice? Which elements still need to be considered? Does the design fit into the relevant environment?

Based on feedback gained from the α-test, the design is adjusted.

The β-test can be considered as an indirect form of action-based research because the designer does not participate directly in the test, (Stam, 2007). During a β-test, a group of practitioners, preferably not involved in the prior empirical studies, uses all or part of the design in practice to discover operational improvements for applying the design. Participating practitioners then are asked to assess the extent to which the application of the design turned out to be valid, usable and productive. Generalisable knowledge is than inductively extracted to adapt the design.

Solution-Focused Applied Psychology

The SoFAP protocol can be applied to the more general area of change facilitation in and between (human) systems and thus transcends the domain of psychotherapy for which the solution-focused approach was originally designed.

The design objective stated in the introduction adds that ‘the protocol should consider the client’s actual context from the start’.

Before applying DSR methodology to generate useful design principles and propositions for SoFAP-P, we will first elaborate on the wording used in the design objective.

First, we want to emphasize that the word ‘protocol’ does not imply a standardized procedure or a uniform ‘one-size-fits-all’ method. Rather it denotes a set of master rules (rules that govern rules at a lower operational level) or instructions that guide the ordering of interventions that a change facilitator can use to work in an effective and efficient manner. The content of the facilitation process comes from the situation in which these master rules can be applied to elicit change and is thus specific to situation X in context Y, with respect to stakeholder(s) Z.

When the term client is used, the reference is always to the client in his relevant context rather than to the internal psychological or intrapsychic mechanisms at play within the client himself. Moreover, the client can be an individual, a couple, family, team, organization as a whole, i.e. a client-system.

With the term problem we indicate a situation, emotion, thought or combination thereof that is hindering one’s functioning and that one wants to get rid of. We are interested in how the practitioner explores together with the client what he or she would like instead of the problem. This exploration usually leads to the formulation of a goal: something the client wants to accomplish, that will help him of her have a better, more fulfilling or at least easier life. A problem has arisen in the present or past. A goal lies in the future. Solution-focused practitioners ask questions that help the client translate goals into challenges. Challenges therefore are drivers towards a solution. A solution is considered here as a (temporary or permanent) situation, emotional and/or cognitive state or a combination thereof that is regarded as ‘good enough to live with’.

In organizational science, productivity is seen as the product of effectiveness and efficiency, (Stack, 2016). Effectiveness implies achieving the intended goal, whereas efficiency indicates a minimal use of resources such as time, money and other means. Therefore, when we say that SoFAP-P needs to help clients address their challenges in a productive way, this also implies that the intended goal is achieved. The protocol we are looking for, cannot sustain the claim of productivity if the existence of a solution is not presupposed. In other words: a valid result of the design objective requires methodologically a solution-focused approach.

As far as the actual context is concerned, the assumption is that – no matter what – helping will be less successful if the client’s ecosystem is not explicitly and directly (= from the beginning) incorporated in the process. The search must be for a protocol that provides direction to any practitioner who wants to help clients with their challenges, and who accepts or is convinced that this cannot be done productively without considering the environment in which the client now lives, loves and works. To use the benefit of short language, from now on we will refer to this environment as the client’s actual context, which represents the current environment of the client, tangible and intangible, including the behavior and interaction patterns of the stakeholders in place.

Given the formulated design objective, it is logical and sensible to explicitly formulate the following three support questions (SQ’s) to be answered by empirical research:

SQ1: What are the characteristics of a solution-focused approach, as opposed to a problem-oriented approach?

SQ2: What is an appropriate area of application for a solution-focused applied psychology protocol to address challenges?

SQ3: What are productivity characteristics of the client-practitioner interaction, in a solution-focused applied psychology protocol to address challenges?

The answers to these questions will support the process of designing the solution-focused applied psychology protocol. The answers will be informed by the design principles and propositions we have identified during the research activities described on page 6 and following and will be answered on page 30.

SoFAP-P principles

The literature study aimed at finding design principles for the envisioned protocol consisted of a broad historical analysis of various methods used in applied psychology (psychoanalysis and psychodynamic approaches; behaviorism and cognitive behavioral therapy; humanistic psychology; family system therapy; Ericksonian practices; solution-focused therapy; and extended solution-focused therapy) that in this article is reduced to the highlights.[1] This reading was complemented with a more specific, targeted reading of relevant literature. In this way, we identified 6 points of attention (PAs) and 14 lessons learned (LLs). Generally speaking, the PA’s refer to shortcomings of historical problem-oriented approaches, whereas LLs were derived from the attempts of alternative models that sought to overcome these shortcomings. Furthermore, consulting our network allowed us to formulate 5 best practices (BPs) in solution-focused psychology and 5 bad practices (BaPs).

Principles drawn from the history of applied psychology

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was one of the first in history to develop psychoanalysis as talking therapy. However, Freud’s seminal books (Studien über Hysterie (1885) and Die Traumdeutung (1899)) show an uncompromising focus on detailed descriptions of psychic problems and their (hypothesized) causes, almost to the point of equating them. This way of thinking proved fruitful in its time. While Freud expanded his theoretical framework, Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) trained a dog to salivate upon hearing the sound of a bell. It served as an illustration to the thought that behavior was biologically determined by cognitional processes from the past and led to a number of behavioral models of psychotherapy, in which emotions where seen as mere physiological expressions that accompanied cognitions. Among these models, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is likely the most renowned. The influence of these movements on the ensuing psychotherapy models led to the formulation of this first Point of Attention.

PA-1: The emphasis in problem-oriented approaches is on the detailed description of problems and corresponding hypothesized causes underlying these problems. These descriptions and the language in which the professional usually converses with the client, are problem oriented. This easily results in a situation where there is (too) little attention paid to finding a solution to solve the client’s problem.

This emphasis on causes is accompanied by a strong tendency to place the problem situation of patients (clients) in a historical context.

PA-2: Most approaches show an unbalanced methodological focus. They pay more attention (= time and energy) to past experiences and to the historical context of the client, than to his present situation and his wishes for change. This goes at the expense of exploring possible future options to bring the desired changes closer.

A first attempt to counter this balance was undertaken by the humanistic approach, that is better described as a general stance than a consortium of intervention techniques. Humanistic psychology opposes the deterministic outlook of earlier theories, further criticizing CBT for its failure to account for fundamental aspects of man as a feeling, thinking, and acting individual. Instead, it was posited, the aim should be for the growth of each individual in terms of fulfillment, self-esteem and autonomy.

LL-1: Abandon analytic classifications of mental problems; focus instead on integrated holistic solutions, (which may be implicitly multi-dimensional and multi-faceted).

This paradigm shift transformed patients into clients, a transformation that was cemented by the book Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory (1951) by the humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers (1902-1987). As the title of the book indicates, the individual was no longer seen as a passive participant in therapy, which suggests some equality between the caregiver and the people to whom care is provided, a stark contrast with practices from other, even more recent, methods.

PA-3: Client’s problem descriptions typically result in classifications of diagnoses and typologies of mental problems and disorders. Such classifications, like DSM V, have the advantage of being convenient, although they can also easily lead to confusion and simplifications that leave little or no room for the complexity of human life, with all its serendipities, unexpected, unfathomable, and unpredictable twists and turns.

LL-2: The client’s goals and resources should be the center of attention. The paradigm the practitioner uses to guide his interventions, is no more than a tool in the client’s facilitation process. So don’t let the method be leading, but the client.

However, the humanistic approach suffered from its own idealism by making clients aim for abstractions. Everyone was to strive for self-awareness, self-enhancement, self-actualization, big words that are hard to do justice in practice.

LL-3: Useful client goals are practical, realistic, achievable, can be phrased in behavioral terms (‘What will you do/think/feel different if…’), and they preferably go from small to large.

LL-4: Start from the client’s present situation as it relates to his momentary goals and then develop a future orientation.

The focus on the self from humanistic psychology brought to light another aspect of human experience that had also been neglected by earlier psychoanalytic models. In Freud’s talking therapy the relevance of the client’s current ecosystem was overlooked, and only served as a canvas on which the neuroticism of the patient was outlined. Neither CBT deemed the social context of the client to be of importance.

PA-4: The problem-oriented theories evaluated, show an unbalanced stakeholder focus: The emphasis of attention mainly goes to the client as an individual, even if the treatment format is the couple, the family, or a group. Other stakeholders in the client’s ecosystem are seen as more peripheral.

The first to recognize this neglect was the school of family systems therapy (FST) that came up after the second world war as a result of the inflow of many psychiatric patients from the battlefield. It was obvious that some relapsed upon returning to their families and communities, while others readjusted and healed with the help of their new surroundings. The idea that the patient’s ecosystem was a factor started to dawn, enabling practitioners to move from the intrapsychic to an interactionist view.

LL-5: Incorporate the client’s actual context directly and explicitly in the approach. This means involving all relevant stakeholders in the client’s actual ecosystemic context in such a way that they can contribute additional resources for the client or that they can benefit from the progress of the client or both.

In the early phase of FST, the family was usually assumed to be the most important subsystem in the client’s actual context. The aim was to look for interactional patterns in the relationships between family members, the idea being that some of these patterns can negatively affect one or more family members to the extent that they experience problems, and how their reactions to these recurring interactions then perpetuate the problematic interactional cycle. The result has been a slightly mechanistic interpretation of the functioning of people and their interactions. This is a problem that can be traced back to the original schools of Freudian psychoanalysis and CBT.

PA-5: The causal linearity from anamnesis and diagnosis to therapy and prognosis, obscures the complexity of each client’s life, oversimplifies the situation that causes the problem and thereby reduces the opportunity for robust and sustainable solutions.

The practice of Dr. Milton Erickson constituted a radical antidote to this pitfall. In his approach, it was always the client’s actual, present context which guided the client’s growth-orientation, while the past only deserved the amount of attention necessary to avoid falling into useless habits. From this focus on the present one can complement the previous point of attention:

LL-6: Refrain from the linearity of anamnesis, diagnosis, therapy and prognosis; work iteratively, recursively and circularly instead.

As stated in the introduction, the practice of Erickson suffered from a lack of transferability that de Shazer and Berg sought to overcome, eventually leading to the teaching of solution-focused therapy (SFT). In de Shazer’s book, Putting Difference to Work (1991) the difference with other forms of therapy and their philosophical underpinnings is clarified by his famous quote, the class of problems belongs to another logical class than the class of solutions. In other words: one does not necessarily need to understand neither the nature nor the underlying root cause of a problem to help the client find a solution. But despite this insight, practitioners in SFT for a long time were unnecessarily hesitant to ask clients directly for their goals and the potential solutions they envisaged. Reflecting on this limitation and some of the principles already extracted above, three lessons were drawn at once.

LL-7: Solutions belong to the future, while problems belong to the past. The emphasis should be towards constructing possible solutions and desired outcomes.

Instead of concentrating on the (why of the) problems in the past, the focus of the practitioner should be on the desired outcome: ‘What do you want to accomplish tomorrow and next week?’, ‘What could be the first little step to achieve this?’LL-8: Solutions can be: 1) outcomes, results, 2) process effects, (since thoughts change actions and vice versa), 3) combinations of 1 and 2.

LL-9: First focus on potential solutions and then iterate intermediate steps to create a robust, self-learning, client-specific solution methodology.

To conclude, it is clear that all of the above deficiencies impede the client’s path to his goals and therefore imply a lack of efficiency in the use of time, money and other resources. This led to the inclusion of a rather formal point of attention:

PA-6: In general, problem-oriented approaches suffer to a greater or lesser extent from a lack of efficiency in the use of time, money and other resources.

Principles drawn from the targeted literature study

Additional design principles were distilled from a pragmatic literature study.

Studying the interaction between practitioner and client, Bachelor (1995) established that the success of their therapy heavily depends on the attitude the practitioner assumes during sessions with the client. Most progress was made when the practitioner’s attitude was attuned to the wishes, goals and learning style of the client.

LL-10: Stimulate a client-driven or -steered approach, instead of a client-oriented or focused one.

As for the term ‘resistance’ from psychoanalysis, we know from de Shazer (1984) that there is no such thing, because anything the client says or does can be interpreted as a directive, instructing the practitioner how the client wants to be helped. In the next lesson learned we have made two frequent instances of ‘resistance’ explicit: a client might be instructed by a third party to see a therapist, or a client might be prejudiced against the idea of having a mental problem.

LL-11: Pay attention to three major tendencies that prevent clients from being open to a solution-focused applied psychology approach: 1) no intrinsic motivation to change, 2) ‘resistance’ to change and 3) translating mental issues into physical problems.

As early as 1936 Samuel Rosenzweig argued that ‘it is justifiable to wonder whether the factors that actually are operative in several different therapies may not have much more in common than the factors alleged to be operative.’ His suggestion (or suspicion) was reinforced by findings from Lambert (1992), who showed that non-specific factors are mostly responsible for changes caused during psychological facilitation: only 15% of changes could be attributed to method-specific interventions, the remaining 85% could be traced back to the relationship between the client and the practitioner, the hopes and expectations of the client for a better future, and extra-therapeutic factors. Furthermore, Frank & Frank (1991) have specified how these important non-specific or common factors can be activated by the practitioner. Two lessons can be learned from this at once:

LL-12a: Integrate the exploitation of non-specific therapeutic factors, seen from the client’s point of view, into the facilitation approach (instead of regarding them as a welcome by-product). Non-specific therapeutic factors are: the client feels that he is understood, receives authentic attention, feels respected and is offered a perspective that gives him hope for change in the future.

LL-12b: Integrate the exploitation of the non-specific therapeutic factors, seen from the practitioner’s point of view, into the facilitation approach.

Wampold (2001) is even more skeptical about the benefit of specific methods than Lambert (1992), stating that no more than 8% of therapeutic outcomes could be seen as the result of method-specific mechanisms. He recommends practitioners are open to the following two lessons. The first is to help the client break free from his binary black and white stance. The second lesson recommends placing the client at the center of the therapeutic process through a carefully developed working relationship.

LL-13: Put the effect of psychological and inter-relational facilitation techniques into a more differentiated perspective by asking differentiation questions (including scaling questions).

LL-14: Allow the therapeutic relationship to develop into a therapeutic alliance.

Lessons learned through structured networking

During many years of collaboration with thought leaders and experts in the fields of psychotherapy, cybernetics, epistemology, hypnotherapy, systems thinking, linguistics, swarm intelligence, and, of course, solution-focused practice, Cauffman as a researcher had the opportunity to spend countless hours co-teaching, learning from, studying, and discussing with those experts. These contacts broadened, contradicted, tested, challenged, confirmed or falsified (in whole or in part), and at least sharpened his views. From that groundwork, the following five Best and Bad Practices for the envisioned SoFAP-P design were distilled.

BP-1: Transform the working relationship with the client into an alliance

A relationship reflects a connection while an alliance is a bond between parties that share a common goal. The psychological practitioner therefore must consider the goals of the client and construct his working relationship into an alliance with the client that is geared towards this goal. The practitioner and his expertise are the tools to help the client help himself, (cf. LL-14)

BP-2: Set goals in an active manner

This Best Practice takes LL-3 one step further. It is necessary to actively ask questions to help the client set his goals and to help him translate them into a list of useful objectives that can serve as a checklist. Useful goals are practical, realistic, achievable, can be phrased in behavioral terms (What will you do different if…) and preferably go from small to large.

BP-3: Set goals in a continuous manner

In psychological facilitation the client is helped to translate his goals into challenges, as was implied by LL-9. Once a partial goal is achieved, this change becomes the context for a follow-up challenge until the mother of all goals is reached: the client is helped to help himself reach his own goals by using his own resources. In brief, goal setting is not a fixed-state intervention (you once set a goal and that is it) but an active, iterative and recursive process.

BP-4: Concentrate on the client’s resources and possibilities

Use the idea and accompanying question: What is going well (enough) despite the problem? to focus - both the client’s attention and the practitioner’s perspective - on the resources that can be used to take steps forward toward a desired future.

BP-5: Use the Minimax Decision Rules.

‘Minimax’ stands for using minimal effort as a practitioner while attaining maximal output and change for the client. It is a useful tool regarding PA-6. Our empirical research among practitioners has shown that most of the experts appear to apply, implicitly or explicitly, the following four basic rules in their work:

-

Rule 1: If something is not broken, do not repair it but show respect and appreciation for what still works.

-

Rule 2: If something does not work, or no longer works, or does not work well enough after trying it for a while, stop, learn from it, and do something else.

-

Rule 3: If something works well, well enough, or better, keep doing it and/or do more of it.

-

Rule 4: If something works well, well enough, or better, then offer it to, or learn it from someone else.

As for the Bad Practices, the main pitfalls appear to be the therapist’s own convictions and theories (Kottler & Carlson, 2003). Indeed, the therapist may be so attached to them that they can be a hindrance to the client. We will just mention the encountered Bad Practices and note that they are in agreement with the points of attention and lessons learned identified above.

BaP-1: Give primacy to a theory, model or method over the idiosyncratic needs and possibilities of the client.

BaP-2: Delve into speculations about the why of what goes wrong.

BaP-3: Have an obsessive focus on the past

BaP-4: Limit the desired goals to the mere absence of problems.

BaP-5: Treat the working relationship as an asymmetric one in which the client is the source of all difficulties and the practitioner is the all-knowing expert.

SoFAP-P propositions (CIMOs)

For the case study, 25 cases were collected from which 21 CIMOs could be extracted. This extraction process was conducted by both researchers/authors separately and independently. Any differences in their outcomes were amply discussed. Whenever consensus could not be reached, the case was presented to a third party working in the field of applied psychology. Most CIMOs that came out of this process are based on multiple indications that occur in several cases.

Here is (part of) one of the 25 cases analysed to illustrate the ‘mining’ of CIMOs. The title of a CIMO is derived from the intervention contained in it and therefore has the character of an imperative: they tell the practitioner what to do.

Case: It is not me. It is him!

The HR manager gets an urgent phone call from one of the production managers who says: ‘Look, can you do me a favor? I have this guy Eric in my team who is driving me crazy. I feel that he is constantly trying to undermine my authority within the team. We have just had a big fight and I told him to go and talk to you to get himself straightened out. I also told him that this was his last chance. If he doesn’t stop his subversive behavior right now, I will kick him out. Can you talk to the guy right now, please? He is on his way to your office.’

HR manager: ‘Is this guy good at his job? Do you really want to get rid of him or, apart from regularly getting on your nerves, is he a doing useful work in your team?’ [cimo-7] [cimo-16]

Production manager (taken aback a little by this question): ‘Well, he is very good at his job. The best there is. The problem is that he knows it, and he feels protected by it. But this time I mean it — get him to shape up or I will ship him out.’

HR manager: ‘Well, that is a very determined, or should I say, black-white position you take. No promises from me but I will talk to him and see what can be done.’

Eric storms into the office of the HR manager: ‘I must come and see you because my boss told me to. He accuses me of undermining his authority within the team behind his back. But that’s a lie. It’s simply not true. He got so angry that he ordered me to come and see you or he would kick me out. I know, when he is under stress, he has a tendency to think digital, black-white. He is an engineer. But now, I think the guy has just lost his marbles. That’s it, I have nothing more to say — it should be him who needs the shrink.’ [cimo-6]

HR manager: ‘Whoa! Have a seat and let’s see what can be done. Tell me what happened, please.’

Eric tells a long and winding story that can be summarized as an avalanche of mutual misunderstandings. [cimo-1] [cimo-3]

After a while, the HR manager says: ‘OK, Eric, I see your point. I don’t feel like getting into all kinds of rationalizations about who is right and who is wrong. You’re only talking to me because you must. And it is my job to talk to you. It is obvious that your boss is upset with you. But, if you look at the positive side of this: he sends you to come and talk to me, which means that he still sees a chance to get out of this mess. Otherwise, he would not make the effort of referring you to me. So, maybe it is helpful to step over the black or white position and try to look at the situation in a more relativistic way. [cimo-17] Eric looks surprised and nods: Yes, you are probably correct. The HR manager continues: Now, let me ask you a question. What do you need to do differently to get your boss off your back?’ [cimo-5] [cimo-7]

It is clear that Eric has no request for help whatsoever on the topic that his boss rises, i.e. his presumed subversive behavior. The HR manager decides not to delve into a fruitless search and analysis for truth: is Eric acting subversively, yes or no? Such an intervention would lead nowhere except towards more trouble. The HR manager points out that the boss, even though he is cross with Eric, still has a positive reason for his referral. [cimo-8] This has a soothing effect. The HR manager’s last question then helps Eric to think about an alternative problem — what does Eric need to do differently so that he no longer has the boss on his back? [cimo-6] Now that is a problem for which Eric might have a request for help. From that point, a useful conversation develops. The HR manager can ask differentiating questions: 'If right now is the very worst situation of the last months, can you give me some examples of moments when it was a little bit easier to deal with each other? What did you do differently and what did your boss do differently? Follow-up questions help Eric to slowly step out of the binary position (yes/no, black/white, on/off) and start talking about what he could do differently to make his dealings with his boss easier. At the end of the conversation, the HR manager asks Eric if this conversation was useful to him. [cimo-16]. Eric responds: 'Yes, you help me see things in a more correct perspective and that is both a relief and a good starting point for the next steps forward.

We will only present CIMO-16 and CIMO-17 here as examples[2].

CIMO-16: Ask the usefulness question

Whenever the practitioner has the impression that his facilitation is not resulting in sufficient progress or that feedback is needed, he should ask the client the following question: Is it useful when we talk like this? This intervention is as powerful as it is elegant and serves to invite the client to view the working relationship from a meta-perspective. The question simply elicits useful feedback from the client while answering does not require specific intellectual capacities. In this sense the question can even be used in conversations with children or people with a mental disability. The goal of this question is to offer the client the chance to give feedback on his own facilitation process which puts him in the center of the alliance.

CIMO-17: Offer a relativistic perspective

When clients have the impression that they are in deep trouble, they often tend to think in black & white terms, which petrifies their vision. Then the practitioner must help them find nuances to counteract this dismal viewpoint. Giving rational counterarguments rarely yields results. To elicit the desired perspective, ask questions or make comments that suggest a more relative perspective. Examples include questions or comments such as: Wouldn’t it be good to sleep on this? Are you sure you’re not exaggerating? The soup is never eaten as hot as it comes out of the bowl. Tomorrow is another day. And so on. One must, of course, be careful to phrase these remarks respectfully and avoid the possibility that they could be interpreted as cynical, trivial or demeaning.

Limitation regarding the CIMO-logic

In ‘mining’ CIMOs from practitioners’ cases, it was decided to focus on making explicit the experiences practitioners have encountered in their interactions with clients. This is done to reduce complexity in the description of the CIMOs. The consequence is that in most cases the Context, the Intervention and the expected result (the Output) are more clearly expressed in the wording of the CIMO than the Mechanism.

Answering the Support Questions

With the information extracted from literature, work with experts, and client cases, the three research support questions (SQs) mentioned at the beginning of section 3 can be answered.

SQ1: What are the characteristics of a solution-focused approach, as opposed to a problem-oriented approach?

Solution-focused applied psychology refers to the overarching approach that acts like an operating system versus concrete interventions and methods from problem-oriented approaches that are like applications. Essentially, the solution-focused way of working is characterized by 8 core features. It is only interested in problems as far as they provide clues to the possible solutions, no problem is static and exceptions in problem perception show the way to improvement (1). There is continuous focus on the available resources that the individual, couple, family or larger system in question can use to move forward in life (2). With the help of explicit questions, attention is channeled towards a future where possible solutions lie (3), this is done with an eye for the goals of the client (4). In the practitioner’s approach questions take precedence over explanations (5) and the minimax decision rules (see: BP-5) are respected (6). The conversations between practitioner and client make use of so-called ‘solution talk’ which is always aimed at helping the client construct an alternative reality to his or her problem state (7). Ultimately, these points go back to the 5 axioms mentioned on pages 2 and 3 and the corresponding image of humankind (8).

SQ2: What is an appropriate area of application for a solution-focused applied psychology protocol to address challenges?

Applied psychology is used, among other things, for study and career advice, in recruitment and selection, consumer marketing, coaching, organizational and family business consulting, school and educational applications, leadership development and, of course, in mental health care. These are all areas were SoFAP-P could be implemented by practitioners. The application of SoFAP-P must also depend on the motivation of the client to be helped by it. In any case, however, problems that cannot be reformulated as a challenge (think of (neuro)physiological defects) are unsuitable targets for the implementation of SoFAP-P.

SQ3: What are productivity characteristics of the client-practitioner interaction, in a solution-focused applied psychology protocol to address challenges?

A productive client-practitioner interaction is reached when the non-specific factors from LL-12a (the client feels that he is understood, receives authentic attention, feels respected and is offered a perspective that gives him hope for change) are optimally exploited. The key to unlock their potential likely lies within the linguistic skill of the practitioner. In a productive client-practitioner alliance, the attitude of the practitioner is marked by his or her continuous evaluation of the language used and interventions made, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Indications and Contra Indications for SoFAP-P

SoFAP-P is indicated, meaning useful, effective, and efficient when the client:

-

agrees to develop a working relationship with a solution-focused practitioner,

-

is able and/or willing to formulate a goal,

-

is open to acknowledging his own resources that can help him to obtain his goal, and

-

is prepared to do the necessary work.

From a practical point of view, SoFAP-P is ideally suited for situations where time- and monetary resources are limited.

Contra-indications for applying SoFAP-P:

-

The most general contra-indication is a client who is completely unable to either communicate or enter a constructive working relationship. Examples include persons so severely intoxicated that -temporarily- no connection is possible with them, persons in a florid psychotic state that totally engulfs them.

-

Clients whose psychological, relational, and communicative abilities are hampered by neurophysiological disturbances. In those cases, the priority lies with an intervention in the underlying substrate to rectify the underlying neurophysiological causality.

-

Situations where it simply is not appropriate and even illegal to apply psychological interventions. When confronted with illegal acts, unethical behavior that is hurtful and/or harmful to others or to oneself, etc. In sum, contraindications that are stated in the deontological codes of the professional.

To conclude: the solution-focused applied psychology protocol approaches clients’ problems as challenges that they can solve by using their own resources to achieve positive results towards their desired goals, independent of problem-focused indications and specific model-driven beliefs.

Protocol for Solution-Focused Applied Psychology

With the design suggestions and principles gathered as illustrated in the previous section, SoFAP-P is designed as an arrangement of interventions that can be applied by professionals in facilitating change in and between (human) systems. Its use is therefore more broadly applicable than the original field of psychotherapy. This protocol does not simply follow as a logical consequence from the aforementioned principles and propositions, but rather is the result of an informed creative leap that was subjected to multiple rounds of iterative testing.

SoFAP-P is designed to guide the conversation between practitioner and client (spanning the length of their facilitating cooperation) and has the overarching structure of a flowchart, consisting of three major Movements[3]. Each movement has several components and the often consecutive, iterative and sometimes recursive paths through these movements and components are chosen by the practitioner with the sole criterion to facilitate positive change for the client. So, the path through the flowchart should be determined by what happens in the working relationship between the practitioner and the client(system).

This flow seldomly is linear but jumps both within each movement as across the different movements. Within each movement, the flow can jump from one component/working relationship type to another as result of the continuously evolving situation. As depicted in the SoFAP-P flowchart, sometimes it is necessary to retrace previous steps or move back to a previous movement. For a further explanation of the 3 Movements, we refer to the Appendix 2.

Often successive steps are applied sequentially and iteratively, and recursively if necessary, allowing for all kinds of variations and ramifications in the intervention process. It may be necessary to return to earlier steps and make subtle changes in them. Then the flow becomes recursive. Yet, since the creation of a reality is a constantly unfolding process, there is no possibility of returning to the exact initial state (πάντα ῥεῖ).

The succession and accumulation of interactive and recursive steps leads to a change process of a cumulative nature.

For a detailed description of the steps and decisions in the SoFAP Protocol, please refer to: Cauffman, L, and Weggeman, M. (Routledge 2023): Solution-focused Applied Psychology. A Design Science Research Based Protocol. Routledge.

The flowchart in Figure 1 is a static visual representation. By scanning the following QR code, you can access an animated version that moves through all the different stages. This dynamic flowchart is a tool for learning, teaching, and intervening.

Discussion and conclusion

Organization science has greatly benefited from the contingency theory as formulated by Jay Galbraith (1973). The theory is based on two assumptions: first that there is no one best way to organize, and second that not all ways of organization are equally effective. For this design task, those assumptions translate as:

-

There is no best applied psychology approach

-

Not every applied psychology approach is equally effective.

Assumption 2 implies that any meaningful discussion of any such approach must be comparative in nature, whereas the first assumption implies that any such comparison must be particular, i.e. based on the experience of practitioners who feel qualified to make a judgement.

In this light, alpha and beta-testing[4] indeed can be considered as particularly well-suited methods to ascertain the pragmatic validity of the SoFAP-Protocol

Validating SoFAP-P

As stated on page 7, as SoFAP-P was being created, it was subjected to α- and β-testing. The results of those tests are discussed here. The β-test will make clear that SoFAP-P is indeed effective (i.e. that the design objective has been met) while the α-test shows that practitioners value the principles and propositions that lie at its base.

A survey on the principles and propositions underlying SoFAP-P

The survey contained 81 multiple choice questions of which 75 were about the building blocks and 6 about the presumed productivity of the solution-focused approach. In the case of the building blocks, participants were asked to rate their relevance on a 5-point Likert scale. Here, relevance was considered an implicit indicator of the pragmatic validity of the building block.

The main conclusion of the survey was that the relevance of each building block on average scored higher than 3.00 on the Likert scale, with 70 scoring a relevance higher than 3.50. What’s more, the standard deviation on almost all questions was low, indicating a strong consensus on the relevance c.q. pragmatic validity of most building blocks.

Finally, the building blocks were drafted roughly in the order in which they are presented from page 10 onwards. The average scores of the different types of building blocks confirm the intuition that as the researchers’ knowledge, necessary for designing the envisioned approach, increases, so does the appreciation of the building blocks they formulate. Average relevance scores by practitioners: Points of Attention = 3.73, Lessons Learned = 4.05, Best & Bad Practices = 4.19, CIMOs = 4.21.

Applying SoFAP-P to real-life cases

For the β-test, four cases from literature on solution-focused psychology were chosen, all four of them meeting the criterion that the interventions of the practitioner had proved productive. It was verified that the conversations that took place during sessions indeed followed the guidance of SoFAP-P. For each case the sequence of interventions could be marked with a red line on the SoFAP-P flowchart from Figure 1. In other words, the course of the facilitation process would have remained unchanged if the practitioner had based his interventions on SoFAP-P. The fact that this could be done at all in each of the four test cases yields a positively valued β-test result.

It would be interesting to extend the β-test to a field test with trained practitioners. If such a test were successful, it would add even more to the validity of SoFAP-P.

Contribution to Practice

SoFAP-P -as it culminates in the flowchart- is designed as a tool to streamline interventions, not as a mandatory standardized one-size-fits-all linear protocol. The inexperienced solution-focused practitioner will attempt to follow the relevant route through the empirically based flowchart as best he or she can. Lacking experience, he will want to rely on codified knowledge and avoid any semblance of magic or charlatanry. When learning to drive a car, one must face the challenge of doing many things at the same time. It takes time and effort to become a fluent driver. The same time and effort is required for a practitioner to become familiar with the flow chart and use it naturally. The experienced practitioner can connect with a client while exploring the relevant context in which the client lives and gather initial ideas about his goals and resources. What is at issue here is the simultaneous (i.e. non-linear) use of relevant tacit knowledge (Polanyi, 1966) by the seasoned practitioner. Eventually SoFAP-P seeks to add lightness to the client-practitioner interaction.

The design will bring a number of benefits to experienced solution-focused practitioners.

First of all, SoFAP-P guides client and practitioner along the shortest path towards the client’s goals, ignoring intuitive side paths: the design minimizes noise by forcing the practitioner to focus exclusively and continuously on the client’s interests. In doing so, the design leaves ample space for the client’s ecosystem to be included in the change process. This was already the case with Solution-Focused Therapy, but even there the invitation of a relevant stakeholder to a therapy session remained rare. Similarly, for a long time, practitioners working with SFT were hesitant to ask their client to explicitly formulate their goals, feeling more comfortable instead to deduce the client’s goals from the context he was providing. The SoFAP-Protocol however combines context-clarifying questions with straight goal setting questions. All of this explains how the protocol contributes to the brevity and efficacy of the solution-focused approach, thus making it a worthwhile investment of time and money.

Conclusion

Besides the benefits mentioned above, this article sets out a clear path for the future development of the solution-focused approach in general. In doing so, it has recognized the importance of moving from the trend of appropriating the legacy of Erickson, de Shazer and Berg in the form of new thought-up, superfluous rituals performed in cult-like settings. At the same time, it can no longer afford any simplifications for the sake of transferability. We stress that if solution-focused applied psychology wants to survive, it needs to find its way back to professional standards. It needs to move back to the idea of the clinic where solution-focused psychology was first used by professionals as a tool (and not as an end in itself) to make a difference in the lives of their clients. This tool needed to be as simple as possible, but no simpler than necessary.

Furthermore, we make clear that the solution-focused approach needs to move forward towards a theoretical grounding, appreciating epistemological complexity, and with the courage to go against novelties that bring no improvement. This contribution, relying heavily on DSR methodology, also sets an example to incorporate research from crosslinked scientific endeavors so solution-focused applied psychology truly becomes a coat of many colors.

All of this will contribute to the acceptance of the solution-focused school in the academic scene, which of course is at the heart of the field problem defined on page 5: the (perceived) lack of validation of the practice of solution-focused practitioners. SoFAP-P not only offers a solution to that problem, but simultaneously serves as a useful guide to unexperienced practitioners who wish to become familiar with the rich epistemology that underlies the solution-focused approach, honoring the human complexity, the intricacies and difficulties of change and the needed linguistic subtleties to facilitate desired changes.

.png)

.png)