The Development of the Solution-Focused Approach

The solution-focused (SF) approach was originally developed as Solution-Focused Brief Therapy in the early 1980s by Insoo Kim Berg, Steve de Shazer, and their team at the Brief Family Therapy Center in Milwaukee. They conducted and researched therapy conversations and empirically investigated which elements of conversations make a useful difference for clients. They discovered that clients made faster progress when the conversations focused on the desired future, on what was already working, and on potential progress. From these observations, they gradually developed and refined the SF approach (De Shazer & Dolan, 2007).

Thanks to its high utility, SF became established not only in therapy but also as a coaching and consulting approach in organizations from the 1990s onwards. For some time now, it has also been successfully applied in leadership (e.g. Burgstaller, 2015; Cauffman & Dierolf, 2007; Czerny & Godat, 2024; Godat, 2013b, 2013a, 2016; Godat & Czerny, 2022; Jackson & McKergow, 2024; Polgar & Hankovszky, 2014).

Solution-Focus as an Interactional Approach

As Korman, De Jong, and Smock Jordan (2020) show, the development of the solution-focused approach has always centred on an interactional perspective and on the co-construction of a useful conversation. In our experience, however, many practitioners are introduced to SF as a question-based or question-driven approach—one in which the conversation is guided by carefully crafted questions. Peter de Jong once shared how, on his way to meet his first clients, he would memorise the questions Insoo Kim Berg asked by listening repeatedly to a tape recording (Czerny & Godat, 2018). We, too, initially learned SF this way. In this view, asking the “right” questions is considered key to navigating the conversation.

As practitioners continue to engage with SF and deepen their understanding, they often discover that the approach is as much—if not more—about listening. It involves deliberately picking up on elements within the conversation partner’s narrative that can facilitate progress (De Jong & Berg, 2013, p. 57). As a result, SF is then often seen as a listening-based approach, where the emphasis shifts from the therapist, coach, or conversation leader to the value of the conversation partner’s contributions and the deliberate selection of these contributions (Czerny & Godat, 2018).

While a question-based approach to SF emphasizes the role of the SF practitioner, a listening-based approach highlights the importance of the conversation partner’s input. Both perspectives tend to focus merely on one person in the interaction or on a turn-taking idea. However, a conversation is much faster and involves at least two interlocutors mutually influencing each other moment-by-moment, each playing an equally vital role (Bavelas et al., 2017). Therefore, we view SF as an interactional approach, where both participants actively contribute to the co-construction and influence the conversation moment-by-moment (Czerny & Godat, 2024; Godat & Czerny, 2022).

In leadership settings, this perspective offers a valuable lens for examining how interactions contribute to collaboration, alignment, and shared progress. Leaders engage in a wide range of formal and informal interactions (Godat, 2013a), each offering opportunities to shape dialogue in ways that promote shared understanding and progress.

Leaders operate within organisational structures, often maintain long-term relationships with employees, and navigate a wide spectrum of interactions—from brief hallway encounters and informal alignment discussions to structured meetings and formal performance reviews. Unlike therapists or coaches, leaders must also consider multiple desired futures simultaneously: their own, those of individual employees, those of the team, and those of the organisation (Godat, 2013a). As a result, they are responsible for setting boundaries and determining when to provide a clear guiding structure and when to draw on employees’ expertise to co-shape the path forward. In our experience, developing the sensitivity to distinguish between these situations and learning how to effectively leverage employees’ contributions is a central leadership challenge.

As defined in Godat (2013b), Solution-focused leaders apply SF deliberately in their leadership practice. They explicitly focus on elements that promote useful change. They do this primarily through questions, formulations, contributions, and listening, by drawing everyone’s attention to the desired future; to what is already working well and moving in the hoped-for direction; to signs of progress; and to possible next steps (Czerny & Godat, 2024; Godat, 2013b, 2016; Godat & Czerny, 2022).

SF Leadership is enacted in diverse ways. It can contribute to useful change wherever people engage in interaction. In practice this includes (see e.g., Burgstaller, 2015; Cauffman & Dierolf, 2007; Czerny et al., 2020; Czerny & Godat, 2024; Dierolf et al., 2024; Godat, 2016; Jackson & McKergow, 2024; Lueger & Korn, 2006; Polgar & Hankovszky, 2014)

-

everyday interactions (e.g., informal conversations)

-

planned interactions (e.g., one-on-one meetings)

-

effective leadership tools (e.g., employee conversations, project evaluations, work planning)

-

meetings

-

coachings

-

workshops

-

longer-term management cycles such as

-

project management

-

management by objectives

-

strategy cycles

-

risk management

-

Our Solution-Focused Leadership Specialist Course

At the University of Applied Sciences in Lucerne, we lead the specialist course “Solution-Focused Leadership” (Fachkurs für Lösungsfokussierte Führung) in German where leaders learn to apply the solution-focused approach in their leadership interactions. To attend the course, participants need to be in a formal leadership position. A formal leadership position is seen as an officially designated role within an organisation that grants a person legitimate authority and responsibility to direct others and make decisions within defined boundaries. Leaders who attend our course come from a wide range of sectors—including social services, business, education, health care, and beyond. The course consists of one module of three days and two modules of two days. In the three days of module 1, participants are introduced to key elements of SF Leadership, including how to conduct supportive leadership conversations with their employees and colleagues. In a supportive leadership conversation, the leader supports the other person with their issue, question, or challenge. These conversations provide a foundational approach for everyday leadership dialogue and enable participants to identify principles that are transferable to other contexts – also to those that demand clarity and decisive structuring.

To make distinctions in leadership interactions visible and to support targeted learning, we use video recordings of actual conversations. As Gerwing (2021) points out, face-to-face conversations are both persistent and ephemeral—while some moments may be remembered, a myriad of details pass unnoticed. At the same time, conversations are both quantum and incremental: even when they generate “A-ha” moments and can thus be described as quantum in the sense of abrupt transitions, they still unfold incrementally, with participants responding to each other moment-by-moment (Gerwing, 2021).

Because of this ephemeral and incremental nature, interlocutors cannot grasp all the details that occur in a conversation without a video recording. Video recordings allow participants to revisit the exact details of their interaction, providing a basis for grounded reflection on what actually happened—rather than what they believe happened.

In the two days of module 2, participants learn how to integrate SF into their everyday leadership interactions and tools. In the two days of module 3, they showcase an SF application that they implemented in their leadership between modules 2 and 3.

The Research Gap and Our Research Goal

The research gap that this study is designed to address lies at the intersection of SF practices; their application in leadership conversations; and microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue, a method to examine communicative behaviours in face-to-face interactions moment-by-moment:

- Limited research on SF in leadership conversations

Although SF training is being applied in leadership development programs, there is a lack of empirical studies analysing how SF influences leadership interactions. Most existing studies focus on coaching or therapeutic contexts, leaving a gap in understanding how SF methods translate into day-to-day leadership interactions.

- Limited microanalysis research of the influences of SF training

Microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue has rarely been applied to examine how SF training influences conversational behaviours, leaving a gap in understanding how SF translates into observable shifts in communication during interactions moment-by-moment. Without such fine-grained analysis, the subtle, incremental changes in interaction may go unnoticed. Moon (2022) examined the efficacy of training in SF coaching by analysing the response patterns of practitioners in training. Microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue was used for content analysis and the Dialogic Orientation Quadrant (DOQ) for functional analysis. To date, however, no study has investigated how SF training influences the interactive functions of Bavelas et al. (2017) moment-by-moment.

- Limited microanalysis research of leadership interactions

Microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue has been used in therapeutic studies to understand the detailed, moment-by-moment co-construction of dialogue. However, its application to leadership interactions is rare. This creates a gap in understanding the granular conversational shifts that occur when leaders adopt SF in their leadership.

- In addition: No microanalysis research of interactive functions in German

Despite the growing body of research on microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue, no studies to date have conducted a microanalysis of interactive functions in German-language interactions. By applying a microanalysis lens to German data, the present study contributes to filling this empirical gap and provides the basis for cross-linguistic comparison in the analysis of dialogue. The conversations were conducted in Swiss German, a set of the German dialect continuum.

This study seeks to address these gaps by using microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue to examine the influence of SF training on supportive leadership conversations in German speaking conversations.

Our research goal is to analyse how the conversations changed over the three days of SF training, by comparing the interactive functions from the first baseline (pre-training) to the second (post-training) recorded supportive conversation.

Thus, we compare:

-

the change in the interactive functions in the two conversations with our hypotheses of how the conversation should change.

-

the interactive functions of the baseline conversation to the interactive functions in the getting-acquainted conversations of Bavelas et al. (2017) and

-

the interactive functions of the second conversation to the miracle dialogues in De Jong et al. (2020).

Research questions

-

How do the interactive functions in supportive leadership conversations change from the baseline conversation without SF input on day 1 to the second recorded conversation on day 3 with SF input?

-

How do our findings compare to the findings of Bavelas et al. (2017) and De Jong et al. (2020)?

Research Method

Since this study aims to explore the impact of SF training on the interactive functions in supportive leadership conversations, we particularly refer to the microanalysis of calibration sequences (Bavelas et al., 2017) and the microanalysis that was used for the Building Miracles in Dialogue study by De Jong et al. (2020). To achieve this, we conducted a microanalysis of six recorded five-minutes conversations: three baseline conversations (first conversations, prior to SF training) and three conversations conducted after three days of SF training (second conversations, post-training conversation).

Microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue was chosen to provide a detailed, moment-by-moment examination of the interactive functions within these conversations, enabling a close comparison of leaders’ and conversation partners’ communication behaviours before and after training.

We applied principles used in both studies (Bavelas et al., 2017; De Jong et al., 2020) – mainly the application of ELAN (a software for analysing audio and video data provided by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics), the definition of an utterance, the assignment of the interactive functions, and the distribution of interactive functions – to supportive leadership conversations, using video recordings to capture the nuanced interplay of visible and audible communication behaviours. The data were analysed using the coding scheme of Bavelas et al. (2017) that categorized interactive functions. This approach allowed us to quantify and compare the shifts in interactive functions from the baseline conversation to the post-training conversation.

Microanalysis of Face-to-Face Dialogue

Traditional research in psychology and communication has often prioritised individuals as units of analysis, seeking explanations in internal states such as intentions, emotions, or cognition. However, as Bavelas (2005) argues, “focusing on the individual is very likely to preclude learning anything about social interaction or even about the effect of social interaction on the variables of interest” (p. 183). In face-to-face dialogue, what matters is not simply what each person does in isolation, but how their actions are coordinated moment-by-moment (Bavelas, 2022).

This perspective contrasts with individualistic theories that attribute meaning to isolated components, such as the words spoken, the speaker’s intent, or the situational context (Bavelas, 2022; Roberts & Bavelas, 1996), and assume that meaning resides solely in the speaker’s intent or the linguistic content of a sentence. Instead, an interactional approach reflects how participants collaboratively shape understanding moment-by-moment. Meaning is understood as what participants mutually create and understand through their interactions (Garfinkel, 1967; Roberts & Bavelas, 1996). This view is foundational to the microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue (MfD) (Bavelas, 2022; Bavelas et al., 2016; Gerwing et al., 2023).

MfD is a research method that was formalized by Bavelas (2022), and by Bavelas and colleagues (2016, 2017). It builds on earlier foundational work including Bavelas et al. (2000), which laid the groundwork for later methodological developments and applications. Its origins are linked to the Natural History of an Interview project (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1987), which provided essential tools for studying face-to-face dialogue. In their article “Microanalysis of Clinical Interaction (MCI)”, Gerwing et al. (2023, pp. 48–52) provide a comprehensive overview of the historic origins of microanalysis of face-to-face dialogue.

Evolving since then, MfD focuses on the detailed and replicable examination of observable communicative behaviours as they occur, moment-by-moment, in a face-to-face interaction. This allows researchers to capture the dynamic, multi-modal nature of dialogue. The analysis considers each utterance within its sequential context, reflecting how participants respond to and build upon one another’s contributions (Bavelas et al., 2016).

The Interactive Functions

A significant development came with the work of Bavelas et al. (2017), which proposed and tested a three-step calibration model for observing how mutual understanding is built in dialogue. The model posits that communication is not just a simple exchange of information but involves a complex, iterative process where each participant responds to and calibrates the contributions of the other. This model is influenced by Mead’s work (1934) and several subsequent authors (Bavelas et al., 2017) as well as the idea of grounding from the 1990s (Clark & Brennan, 1991), which describes how people in dialogue seek and provide evidence of mutual understanding.

Bavelas et al. (2017) described a detailed observational procedure that includes 15 interactive functions that serve different roles in the calibration process. While these functions were originally developed to enable the identification of calibrating sequences, they can also be used independently to describe and compare patterns of interaction across different types of conversations. In our study, we focused exclusively on the interactive functions themselves to examine how their distribution and use differed between supportive leadership conversations conducted before and after solution-focused training. This allowed us to explore potential shifts in conversational practices without analysing full calibrating sequences.

A description of each of the 15 functions (Bavelas et al., 2017, pp. 100–102) follows in Table 1.

These functions collectively show how both participants in a dialogue actively contribute to and build on each other’s contributions, creating a dynamic and interactive process of mutual understanding (Bavelas et al., 2017).

Hypotheses

Before analysing the six supportive leadership conversations, we developed the following hypotheses of how the interactive functions should change from conversation 1 (pre-training) to conversation 2 (post-training) which follows in Table 2.

We did not make hypotheses about the following interactive functions, which are foundational to general conversational coherence, yet not specifically targeted by solution-focused training in the first three days of our training:

-

(4) Alerting that Repair is needed

-

(6) Scripting

-

(9) Accepting the Proposal

-

(10) Following the Script

-

(12) Assessing What the Other Person Said

-

(13) Confirming What Was Just Said

-

(14) Linking

-

(15) Acknowledging

We thought that observed changes in these functions would more likely reflect situational or interpersonal dynamics than the influence of the solution-focused training.

Research Design

To investigate the impact of SF training on leadership conversations, this study adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative microanalysis with quantitative coding and analysis to examine shifts in interactive functions before and after training. By analysing six leadership conversations—three conducted prior to SF training and three conducted after—the research design aims to capture both the measurable changes after SF training on leaders’ and conversation partners’ interactive functions, and the more nuanced interactive shifts. Particular attention is given to interactive functions directly targeted by SF.

Interview Sample

The study was conducted within the context of the specialist course “Solution-Focused Leadership” (Fachkurs für Lösungsfokussierte Führung), offered at the University of Applied Sciences in Lucerne that started in 2021. There were 13 participants, all of whom were leaders seeking to enhance their leadership skills through the SF approach. Eight participants had prior experience with conversation-based training, such as coaching, social work, or similar disciplines. For one participant the previous training was unclear, while four had no such prior training.

We combined a targeted sampling strategy with a random sampling strategy. To isolate the influences of the training, we included the four participants with no prior training and randomly selected three of them. This ensured a clearer understanding of the training’s influence, as these participants would be less influenced by prior conversational training. The resulting sample thus allowed for an analysis of the shifts in interactive functions after three days of SF Leadership training.

Two Video Recorded Conversations

To examine how conversations changed with the introduction of SF elements, we analysed two video-recorded conversations from each participant with ELAN. The first conversation, a baseline conversation, was recorded on day one of the course before any SF training had been introduced. This baseline interaction served as a starting point for understanding participants’ natural conversational tendencies without exposure to SF. The second analysed conversation took place on day three, after participants had undergone three days of intensive SF training consisting of

- the difference between SF and a problem-focused view

-

an introduction to the interactional view

-

SF assumptions

-

how to navigate SF conversations

-

SF co-construction with concepts in questions and their answering spectrum

-

formulations

-

the SF conversational phases

-

scaling

-

SF listening

-

SF Leadership interventions

-

the exploration of where SF could be applied in their everyday leadership practice

Two participants engaged in a 5-minute supportive leadership conversation as part of the course activities, in which one participant supported the other with their issue, question, or challenge. A third participant recorded the conversation. The trio carried out this activity in one of the designated group rooms. Both participants involved in the recorded conversation consented to having their recording shared with us for research purposes.

The participants were provided with the following instructions regarding the setting:

-

“Form groups of three and go to one of the reserved group rooms.”

-

“In each group, two participants conduct a 5-minute supportive leadership conversation while the third person records the conversation using the mobile phone of the leading participant.”

-

“Position yourselves so that both participants in the conversation are visible on screen from head to torso at all times.”

-

“Regardless of where you are in the conversation, stop after 5 minutes and rotate roles so that each participant has the opportunity to serve as the leading participant, the supported participant, and the recording participant.”

They also received specific instructions for conducting the supportive leadership conversation:

-

“The participant who leads the conversation is tasked with supporting their counterpart’s issue, question, or challenge during the conversation, as they would in their professional role as leaders when approached by an employee or a colleague seeking support.”

-

“The supported participant selects a real issue — something you genuinely wish to address or make progress in your professional context.”

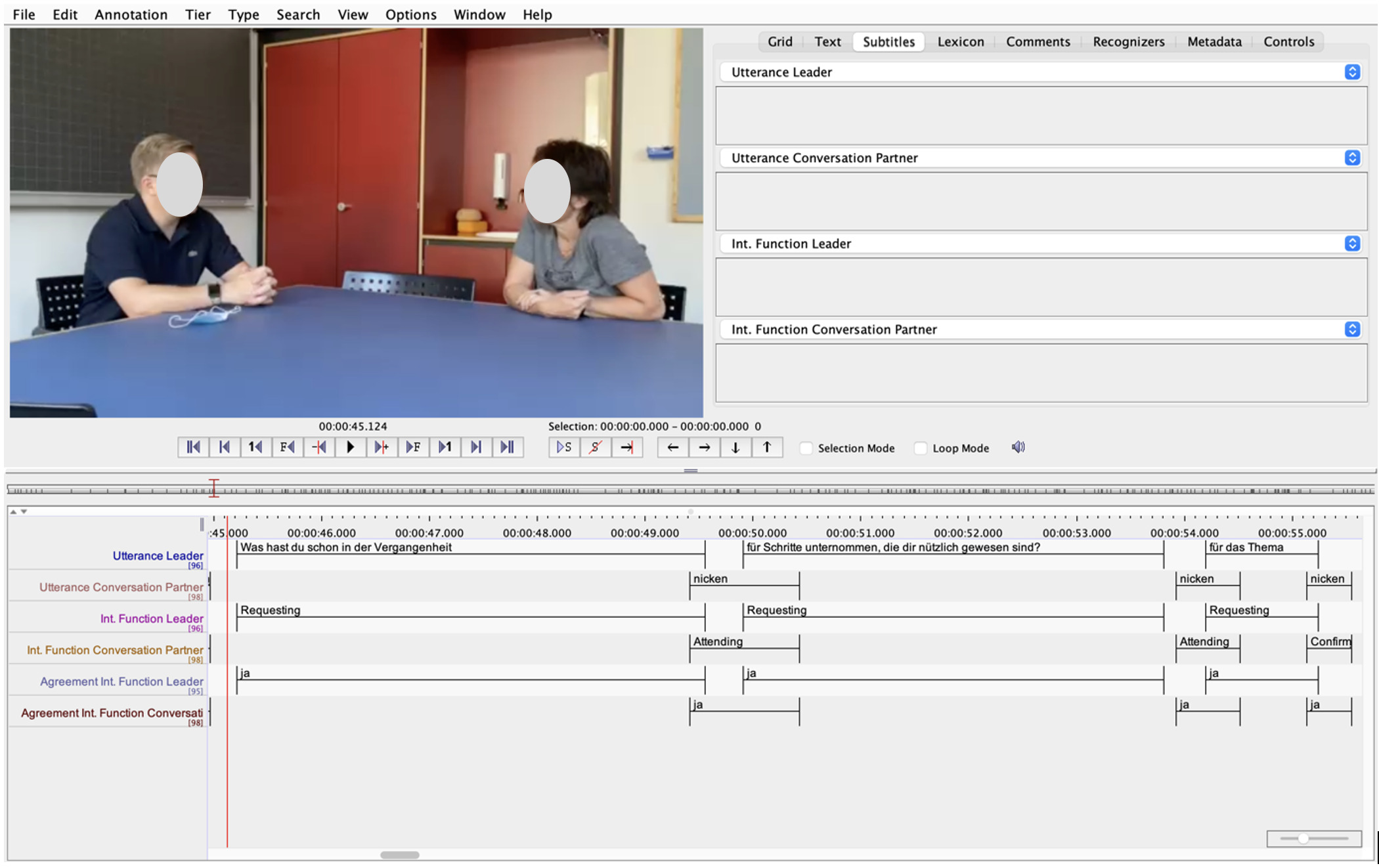

Transcription and ELAN

The transcription process was a crucial step in analysing the recorded conversations. We, the two authors, manually transcribed each conversation in detail, focusing on capturing all utterances. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the transcriptions, each conversation was transcribed independently. After completing our individual transcriptions, we compared our versions line by line to resolve any discrepancies and achieve a final, agreed-upon transcript for each recording.

The finalized transcripts were then imported into ELAN, a professional tool for annotating and analysing audio and video data. ELAN is available for free from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, the Netherlands (http://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan/). It is a multimedia software for viewing video from frame-by-frame to double time and for annotating it on multiple layers called “tiers” that are synchronized with the video. ELAN allowed for a detailed moment-by-moment microanalysis of the conversations, enabling the coding of the interactive functions.

Analysis Procedures: Annotations, Alignment, and Interrater Reliability

We, the two analysts, had to make two decisions: (1) where each utterance began and finished; (2) the interactive function of each utterance. To assess reliability, we both made the same two decisions for each utterance separately so that our decisions could be compared to those of the other analyst.

The analysis proceeded incrementally. First, we identified the precise start and end points of an utterance individually. We defined an utterance in accordance with Bavelas et al. (2017, p. 99):

“An utterance included audible actions (speech, prosody) integrated with what interlocutors were conveying in concurrent co-speech acts (i.e., facial gestures, hand gestures, gaze). An utterance could also be solely visible (e.g., a nod, smile, or raised eyebrows) and could range from a quick nod or a single word to one or more sentences. The end of an utterance was determined by the actions of both individuals: A speaker’s utterance ended either when the speaker paused and looked at the addressee, creating a gaze window to elicit a response (Bavelas et al., 2002) or when the addressee said or did something that could be construed as communicative (e.g., a formulation, ''M-hm”, or a nod)."

After this step, we compared and resolved any discrepancies to get final, agreed-upon utterances for each of the six recordings. We then annotated each utterance individually and assigned interactive functions. One utterance could potentially have more than one interactive function. When this happened, we counted all interactive functions. After this second step, we again compared and resolved any discrepancies for each of the six recordings.

We, the two analysts, working independently reached the following high levels of agreement:

-

97.73 % for where each utterance began and finished and

-

96.52 % for the interactive function of each utterance.

Chi-Squared Tests as Exploratory Indicators of Change

To explore whether the distribution of interactive functions changed after the three-day solution-focused leadership training, we conducted a series of Chi-Square tests. The primary aim was to explore whether the frequency of specific interactive functions differed between the pre- and post-training conversations. The data consisted of discrete, nominally coded categories derived from moment-by-moment microanalysis, making the Chi-Square test an appropriate choice for evaluating potential changes in categorical frequency distributions.

Each interactive function was tested independently using a 2×2 contingency table, comparing the number of times the interactive function occurred in pre- versus post-training conversations with the number of all other interactive functions. This setup aligns closely with the typical design requirements of the Chi-Square test, which is well-suited for detecting distributional shifts in count data across categorical conditions. The test allowed us to determine whether the observed differences were unlikely to be due to chance alone, providing statistical grounding for our exploratory hypotheses.

While the Chi-Square test assumes the independence of observations, this assumption is not fully met in our study due to the interactional and time-bound nature of conversation data. Utterances in dialogue are not isolated but sequentially and socially embedded. Accordingly, we interpret the p-values not as definitive evidence, but as exploratory indicators of potentially meaningful shifts. This cautious interpretation is explicitly reflected in our terminology—referring to outcomes as “suggestive differences” rather than “statistically significant effects.”

Alternative statistical procedures such as t-tests, ANOVAs, or logistic regression were considered inappropriate due to the non-metric, non-continuous nature of the data and the small sample size (six conversations). The McNemar test, while suitable for paired nominal data, was also deemed inapplicable as our analysis was conducted at the level of aggregated function counts rather than matched utterance pairs. Thus, despite the limitations inherent in conversational data, the Chi-Square test provided a pragmatic and methodologically coherent approach for capturing and quantifying the hypothesised shifts in interactive behaviour.

In summary, the use of Chi-Square tests in this study served as a statistically grounded yet exploratory tool to detect functional shifts in interaction patterns associated with solution-focused training. It enabled us to move beyond purely qualitative description and offer initial quantitative support for the change in interactional functions in leadership dialogues.

Key Changes of Interactive Functions Across All Conversations

In presenting the findings of the study we focus on the impact of solution-focused training on the interactive functions of supportive leadership conversations. The results highlight aggregate findings across all conversations.

Across all six conversations, a total of 1,023 utterances were analysed: 513 utterances by leaders and 510 utterances by conversation partners. The conversations spanned 29 minutes and 58 seconds in total.

Below is an outline of the shifts in interactive functions observed between the first and second conversations:

-

(1) Requesting New Topical Content

-

by the Leaders: Increased from 18 to 34.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Remained stable at 0.

-

-

(2) Contributing New Topical Content

-

by the Leaders: Decreased from 78 to 18.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 146 to 173.

-

-

(3) Proposing

-

by the Leaders: Increased from 2 to 7.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Remained stable at 3.

-

-

(4) Alerting that Repair is Needed

-

by the Leaders: Remained at 0.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 0 to 3.

-

-

(5) Reintroducing

-

by the Leaders: Decreased from 9 to 1.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Decreased from 2 to 0.

-

-

(6) Scripting:

-

by the Leaders: Increased from 0 to 4.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Remained at 0.

-

-

(7) Formulating

-

by the Leaders: Decreased from 11 to 3.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 0 to 1.

-

-

(8) Reiterating

-

by the Leaders: Increased from 0 to 1.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Remained at 0.

-

-

(9) Accepting the Proposal

-

by the Leaders: Remained at 0.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 0 to 1.

-

-

(10) Following the Script

-

by the Leaders: Remained at 0.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 0 to 2.

-

-

(11) Attending to the Other Person

-

by the Leaders: Increased from 139 to 155.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Decreased from 76 to 24.

-

-

(12) Asssessing What the Other Person Said

-

by the Leaders: Decreased from 2 to 1.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 1 to 4.

-

-

(13) Confirming What Was Just Said

-

by the Leaders: Increased from 9 to 17.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Decreased from 29 to 14.

-

-

(14) Linking

-

by the Leaders: Decreased from 1 to 0.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Increased from 2 to 3

-

-

(15) Acknowledging

-

by the Leaders: Reduced from 3 to 0.

-

by the Conversation Partners: Reduced from 12 to 11.

-

The comparison between the two conversations revealed six interactive functions with suggestive differences, five of which aligned with the formulated hypotheses:

While none of the results should be interpreted as statistically significant in the strict sense, six of the 30 analysed interactive functions showed differences that, based on exploratory Chi-Square testing, may suggest shifts in conversational behaviour between pre- and post-training interactions:

-

Leaders reduced their (2) contribution of new topical content as well as their (5) reintroducing and increased their (1) requesting and (11) attending.

-

The conversation partners (2) contributed more content, while their (11) attending decreased.

The remaining functions did not show differences that would suggest meaningful shifts based on the exploratory Chi-Square tests. For several functions a test was not applicable because both conditions contained only zero counts or had zero variance—a statistical requirement for the Chi-squared test.

For the individual analysis of the conversations of leaders 1 to 3, please visit Appendix 1 to 3.

Supported Hypotheses

Based on the comparison of the six conversations the following five hypotheses were supported by the findings across all participants:

- Increased (1) Requesting by leaders

Hypothesis: Leaders increase their use of requesting new topical content after solution-focused training.

Findings: The hypothesis was largely supported. Overall, the increase in requesting showed a suggestive pattern of change based on the exploratory Chi-Square analysis. Across all participants, requesting nearly doubled. However, in the conversations of leader 2 requesting remained stable.

- Reduced (2) Contributing by leaders

Hypothesis: Leaders decrease their contributions of new topical content after solution-focused training.

Findings: This hypothesis was largely supported. After training, leaders contributed notably less new content, while conversation partners showed an increase in contributing consistent with suggestive differences identified in the exploratory analysis. However, in the conversations of leader 2 contributions increased, while the conversation partner’s contributions decreased slightly, diverging from the expectation.

- Enhanced (11) Attending by the leader

Hypothesis: Leaders increase attending (e.g., minimal responses like “mhm”) after solution-focused training.

Findings: This hypothesis was largely confirmed overall. The exploratory analysis revealed a suggestive increase in attending by the leaders, who exhibited more attending post-training. However, in the conversations of leader 2 attending even decreased.

- Increased (2) Contributing by the conversation partner

Hypothesis: Conversation partners contribute more new topical content after SF training due to the leaders’ increased requesting.

Findings: This hypothesis was largely confirmed overall. The exploratory analysis indicated a suggestive increase in contributing by the conversation partners, who provided more new content in the post-training conversations. However, in the conversations of leader 2 the conversation partners’ contributions decreased slightly, diverging from the expectation.

- Decreased (11) Attending by the conversation partner:

Hypothesis: Attending of the conversation partners decrease after SF training. While the leaders ask more questions, they also contribute less in the second conversation. The conversation partners contribute more, listen less and therefore attend less.

Findings: This hypothesis was largely confirmed overall. The exploratory analysis indicated a suggestive decrease in attending by the conversation partners. As leaders contributed less new content after training, conversation partners responded by contributing more and attending less. In the conversations of Leader 2, however, the attending of the conversation partner increased slightly.

The confirmed hypotheses show that solution-focused training influences shifts in leadership conversations toward more (1) requesting, (2) reduced leader contributions, and more (11) attending (and thus enhanced listening) by the leader. Overall, leaders enable conversation partners to (2) contribute more actively, not needing to (11) attend as much as before.

While Leader 2’s results diverged in some areas, the overall findings highlight the potential for SF training to transform leadership communication. Future research could investigate contextual variables influencing deviations, as well as long-term impacts of SF training on leadership interactions and implications for organizational outcomes and longitudinal effects of SF training.

Not Supported Hypotheses

While five hypotheses were supported, three of them could not be confirmed based on the overall data. Below is an overview of hypotheses that were not supported:

- Increase in (7) Formulating by Leaders

Hypothesis: Leaders increase their use of formulating after solution-focused training.

Findings: This hypothesis was not supported. The exploratory analysis did not reveal a suggestive difference in formulating. Across all conversations, formulating by leaders even decreased instead of increased.

- Increase in (5) Reintroducing and (8) Reiterating

Hypothesis: Leaders increase the use of reintroducing or reiterating content to build on earlier points after solution-focused training.

Findings: This hypothesis was not supported. The exploratory analysis did not indicate a suggestive change in Reiterating. While the change in Reintroducing reached suggestive significance, the direction of change was contrary to expectations—it did not increase. Reintroducing and Reiterating decreased for all leaders.

- Increase in (3) Proposing

Hypothesis: Leaders increase their use of proposing as they became more skilled at facilitating solution-focused dialogues.

Findings: This hypothesis could not be conclusively supported. The exploratory analysis did not indicate a suggestive change in Proposing. Proposing was infrequent both before and after training, suggesting that after three days of SF training proposals were not in the centre.

The unsupported hypotheses reveal important nuances in the influence of SF training, which could be further explored with future research.

Comparing Our Findings with the Building Miracles in Dialogue Findings

Our findings align with the findings discussed in the Building Miracle Dialogue article (De Jong et al., 2020).

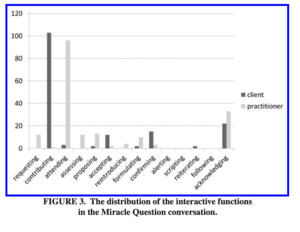

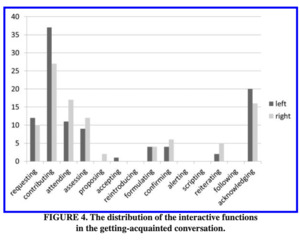

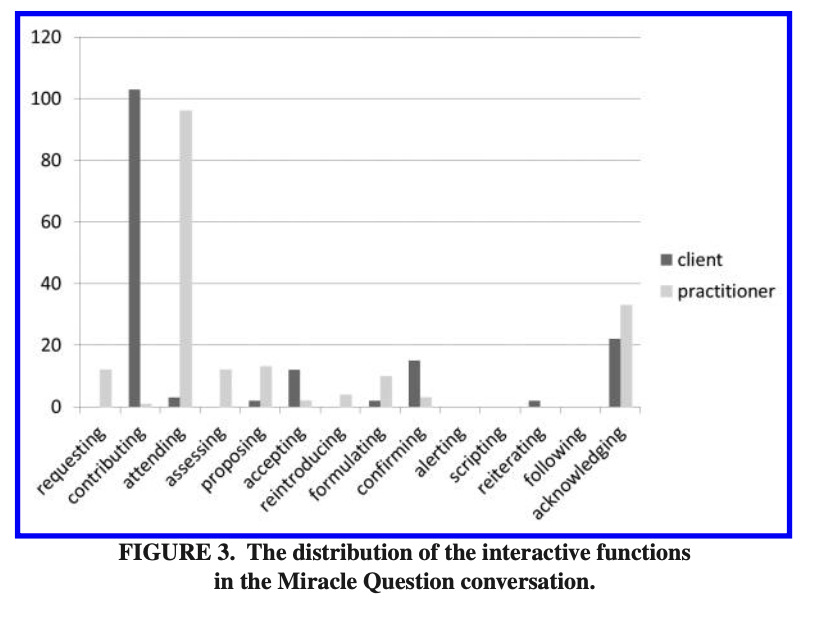

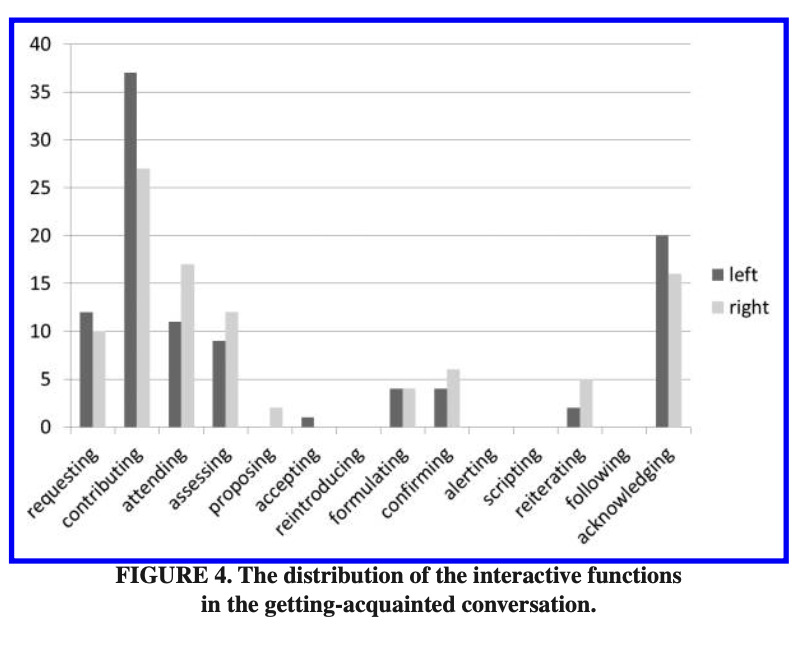

Comparing Figure 3 and Figure 4 with Our Findings

This section outlines key parallels between our results and the findings presented in figures 3 and 4 in De Jong et al. (2020):

- More asymmetry in solution-focused conversations

In general, more asymmetry in the distribution of interactive functions in solution-focused conversations was observed. In the miracle question conversation (figure 3) as well as in our post-training conversations, functions like requesting, contributing, and attending were mostly performed by one of the conversation partners. While in the getting-acquainted dialogues (figure 4) and our baseline conversation the distribution was more evenly distributed with both interlocutors e.g. asking and contributing more evenly (De Jong et al., 2020).

- More attending, less contributing in solution-focused conversations

In the miracle question conversation (figure 3) the therapist attended more to the client’s contributions rather than introducing new topical content while in the getting-acquainted conversations (figure 4) both conversation partners contributed topical content more evenly while also engaging more evenly in attending (De Jong et al., 2020). This shift is also reflected in our post-training and baseline conversations. Leaders also increased their attending and reduced their own topical contributions, while their conversation partners contributed more and attended less in the post-training conversations. In the baseline conversations, as in the getting-acquainted dialogues, leaders contributed more new content and showed less attending than in the post-training dialogue while their conversation partners contributed less and attended more.

- More difference in requesting in solution-focused conversations

In the miracle question conversation (figure 3) only therapists engaged in requesting while in the getting-acquainted conversation both interlocutors asked a similar number of questions (figure 4) (De Jong et al., 2020). This bigger difference in requesting can also be seen in the overall comparison of our post-training conversations with the baseline conversations with leaders asking more questions in post training conversations.

The alignment between our studied conversations and the findings presented in De Jong et al. (2020) and Bavelas et al. (2017) becomes even more compelling when we consider that all supportive leadership conversations in our study were conducted under identical instructions. In Bavelas et al. (2017) and De Jong et al. (2020), the two types of conversations were explicitly constructed with different goals and framing. Still the baseline conversation closely resembles the functional patterns observed in getting-acquainted conversations, while the post-training conversation—following solution-focused training—exhibit patterns akin to those found in miracle-building dialogues. This suggests that the shift in interactive functions is not merely a product of differing instructions but of a shift from a non-SF everyday conversation to an SF conversation.

Comparing Our Findings with Additional Findings in Building Miracles in Dialogue

Beyond the comparison of interactive function distributions illustrated in figures 3 and 4, other findings from the Building Miracles in Dialogue article (De Jong et al., 2020) provide important points of comparison with our study. Below, we highlight the similarities between our findings and the broader insights discussed De Jong et al. (2020):

Co-construction of meaning

The article Building Miracles in Dialogue emphasizes that the dialogue in miracle question conversations is inherently co-constructed, with the therapist and client collaboratively building meaning through iterative sequences. Utterances frequently serve overlapping interactive functions, such as contributing new topical content while simultaneously attending to prior content. This co-construction process was central to creating the client’s “miracle description” (De Jong et al., 2020). Even though we didn’t conduct a full calibration analysis, in our study, this co-construction process of meaning-building can also be seen, e.g. with leaders asking questions and attending more and thus influencing the contributions and co-constructing of meaning.

Overlap of interactive functions

A notable observation in De Jong et al. (2020) in line with Bavelas et al. (2017) is that single utterances often fulfil multiple interactive functions. For example, a therapist’s question might simultaneously contribute new content and attend to the client’s previous statement. This overlap demonstrates the efficiency of solution-focused dialogue in fostering co-construction (De Jong et al., 2020). While overlapping functions were not explicitly analysed in our study, a similar effect can be seen when looking at the ELAN annotations. Thus, an utterance where the leader simultaneously nods or says “mhm” before asking “What else?” can be seen as attending and requesting together. When this happened in this study, we counted all interactive functions.

Rapid calibration sequences

De Jong et al. (2020) noted that calibration sequences in miracle question dialogues are rapid, typically lasting only a few seconds. This temporal efficiency enables the client and therapist to build shared understanding in a fluid and dynamic manner.

While our study did not explicitly measure the duration of calibration sequences, in the observed six conversations the interlocutors made on average an utterance every 1.76 second (1023 utterances in 29 minutes and 58 seconds) indicating that the three-step calibrating sequences were made on average less than every 5.3 seconds. This compares well with both studies that measured an average of 5 seconds and 6.3 seconds per calibration sequence (De Jong et al., 2020).

Purpose-driven differences in interactive functions

De Jong et al. (2020) highlight the influence of the conversational purpose—doing therapy versus getting to know each other that affects the distribution of interactive functions for the participants. The therapist is supposed to ask questions and listen while the client answers whereas the informal purpose of the getting-acquainted dialogue fosters more symmetry of both interlocutors asking, listening and contributing. Even though in our study the purpose was in both conversations similar– to support the conversation partner–the purpose changed in our training from giving advice to seeing the other person as expert and thus asking more questions and listening more attentively. Thus, our results align with this observation. Post-training conversations, shaped by the SF purpose of asking more solution-focused questions and listening more attentively, showed a clear asymmetry in functions whereas baseline conversations reflected a more symmetrical distribution.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the influence of SF training on supportive leadership conversations. Within three days leaders shifted from a supportive leadership conversation where they contributed more to asking more questions and attending more in post-training conversations. This while the conversation partners contributed more and attended less.

However, the observed variability among individual participants, such as Leader 2’s unexpected increase in leader contributions post-training, suggests that contextual factors may influence how SF is adopted in a three-day training setting.

Implications

The study’s results have broad implications for understanding and applying SF in leadership contexts:

-

Seeing employees as experts: The increased requesting and attending suggest that solution-focused training can foster leadership conversations where leaders see the conversation partners as expert for their lives and thus asking more questions and listening better, ultimately enhancing engagement and shared ownership of conversational outcomes.

-

Facilitating leadership conversations: The reduction of the leaders’ contributions in solution-focused conversations challenges traditional leadership paradigms centred on the leaders’ knowledge. Instead, it emphasizes a facilitative role where leaders engage employees more so that they can contribute their expertise.

-

Addressing contextual factors: Variability in individual results highlights the need to address contextual factors when designing solution-focused trainings. Further research could explore how these factors influence the uptake of SF or how trainings could integrate contextual factors more.

The findings suggest several actionable insights for SF Leadership training programs:

-

Emphasizing the co-construction process: Solution-focused conversations, like all other conversations, are rapid and co-constructed with both interlocutors contributing to the story that unfolds. In SF supportive leadership conversations, the leader contributes to this co-construction more with requesting and attending, while the conversation partner contributes more content. SF trainings should shift from addressing SF as a question-based or a listening-based approach to an interactional approach where both interlocutors contribute to the co-construction process.

-

Emphasizing requesting skills: Training modules should prioritize developing leaders’ abilities to see their conversation partners as experts and to ask more solution-focused questions. While this is the case in most SF trainings, it is not usual in leadership trainings. In this more SF way, leadership conversations shift the focus more to conversation partners’ contributions, enabling them to articulate and explore possible solutions.

-

Practicing deliberate listening: Attending plays a critical role in fostering mutual understanding. Leadership training programs should incorporate components that strengthen participants’ capacity to listen attentively and respond deliberately. Prior interactional research (e.g., Bavelas, Coates, et al., 2000; Goodwin, 1986; Tolins & Fox Tree, 2014) demonstrates that minimal responses signalling attention—such as nods or vocalisations like “mhm” (defined in this article as attending)—influence how conversations unfold. By becoming aware of these observable, yet easily overlooked, contributions to the interaction, leaders can more deliberately participate in shaping dialogue and co-constructing meaning.

-

Addressing variability with video analysis: Video analysis of participants’ solution-focused (SF) conversations can reveal differences in how SF elements are adopted, allowing for tailored approaches.

Limitations

While the findings provide valuable insights, the study has several limitations:

-

Sample size: The analysis was limited to six conversations, which may not fully capture the diversity of possible supportive leadership conversations.

-

Training not leadership: The study was performed in a training setting and not in the everyday life of the leaders.

-

Short training duration: The impact of SF training was assessed after three days. Longitudinal studies could provide a deeper understanding of how these skills evolve and are sustained over time.

-

Only supportive leadership conversations: The study’s findings may not be generalized to all leadership contexts, particularly those outside the scope of supportive leadership conversations.

-

Contextual factors: The study did not explicitly account for external factors, such as the nature of the leader-conversation partner relationship or organizational culture, which could influence conversational dynamics.

-

Only functions, not content: This study only analysed the interactive functions and not the content of what was asked or said. Therefore, the quality of the solution-focused questions, the formulations, or the listener responses cannot be determined this way. Although the differences in Leader’s 2 interactive functions might indicate a less SF post-training conversation, this can only be determined with a content analysis.

-

Only suggestive evidence: It is important to note that the assumptions of the Chi-squared test — particularly the independence of observations — are not fully met in this context. Since the data represent interactional behaviour from six distinct conversations (rather than many independent observations), the resulting p-values should be interpreted with caution and understood as indicators of potentially meaningful patterns rather than strict statistical evidence.

Further research could build on this work by examining the effects of solution-focused training with more conversations: in a longer-term training; in everyday leadership settings instead of a training setting; in diverse leadership contexts; taking contextual factors into account; and by doing a content analysis, e.g. of the questions and the answers.

Summary

This study shows that even a short three-day SF training can measurably influence supportive leadership conversations. After three days of training, leaders overall engaged more in asking questions (requesting), in contributing less topical content (contributing) and listening more attentively (attending), while their conversation partners contributed (contributing) more topical content and listened less (attending).

However, not all participants showed the same patterns. For example, one leader increased their own contributions after training, underscoring the role of contextual factors in the adoption of SF practices.

These findings also resonate with previous research. Like De Jong et al. (2020), who analysed how therapist and client co-construct a “miracle description” in an SF therapy conversation, our study found an asymmetrical distribution of interactive functions post-training—with leaders engaging more in requesting and attending while conversation partner contributed more. Compared to the more balanced interactive function distribution of pre-training supportive leadership conversations and getting-acquainted conversations (Bavelas et al., 2017), the shift in our data supports the idea that SF dialogues foster a purposeful change in interactive functions.

These results provide a valuable foundation for further development of SF-based leadership training and open directions for future research—especially in real-life contexts, in longer training settings, with larger samples, in diverse leadership contexts, and including content-level analyses.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Institute of Business and Regional Economics at the University of Applied Sciences Lucerne for partially funding this research. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025) and DeepL (www.deepl.com) for language suggestions and text refinement. Final responsibility for the content lies with the authors.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)