Solution Focused Practice

The emergence of solution focused practice (SFP) as a psychological approach during the 1980s was driven by the work of Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg at the Milwaukee Brief Family Therapy Centre (Langdridge, 2006).

Considered unique, it differs in comparison to more commonly used talking therapies in that the focus is not predominantly on the formulation and understanding of the problems and their root cause (Iveson, 2002). Furthermore, the therapist does not hold expert knowledge on the client’s difficulties and there is no specific focus on formal assessment. The key is the facilitation of conversation to assist the client in identifying their own answers and outcomes (Rhodes & Jakes, 2002) through the exploration of goals, aspirations and the co-construction a new possible reality (O’Connell, 2003).

SFP is underpinned by Social Constructivism with its focus on understanding interpersonal relationships and systemically created knowledge (Bannick, 2007). Additionally influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein’s concept of the ‘language game’; a philosophical viewpoint that builds the belief in the reality of the solution through an unfolding conversation (Ratner et al., 2012), the subjective and social nature of knowledge emphasises that truth and reality are a socially and culturally accepted construct, rather than objective and fixed (O’Connell, 2005).

“People are both constructed by, and constructors of, reality”

Autism and SFP

Autism is defined as a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition characterised by persistent social communication difficulties, sensory sensitivity, having highly focused interests, repetitive behaviour and routines (Autistica, 2020).

Given its philosophical underpinning, with particular emphasis on the use of language to co-construct (Lee, 2013), it could be assumed that SFP may not be as effective when working with autistic individuals and could be seen to have similar excluding factors as more commonly used talking therapies such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

However, when holistically scaffolded and communication adapted, an area initially explored by Mattelin and Volckaert (2017), SFP has the potential to enable the use of a child’s own ‘inner process’ to develop and facilitate potentially significant changes in an environment or area of their life in which they have little to no control (Shapiro, 1994).

The approaches utilised within SFP align with and lean into several autistic characteristics:

-

A focus on specific desired outcomes, with an emphasis on what the individual wants to happen.

-

Solutions which do not necessarily directly “fit” the problem, but instead fit the client.

-

The use of therapeutic pauses and silence, which supports processing and allows time for thinking (De Shazer et al., 2021) as it can take an autistic person longer to process a verbal question (Mayes & Calhoun, 2007).

These elements share similarities with teaching approaches used to support autistic pupils and led the researcher to consider whether SFP could be effective within an educational environment.

This retrospective case study sought to explore if SFP could be utilised within a primary education setting to support the well-being of an autistic pupil when individually adapted to support their communication style. The aim was to observe if the autistic pupil would engage with and respond to SFP within an educational environment with a safe and familiar adult, in this instance, their teacher.

Case Description

Client Background

Pseudonyms have been used for confidentiality and anonymity.

Jo was an 8-year-old autistic pupil who had attended a specialist support school since reception. Their learning environment was scaffolded to support their information processing, understanding of emotions, retention, recall and executive functioning skills in the form of a differentiated curriculum, additional adults and visual supports.

Jo was described within the education system as working “at levels substantially below those expected of pupils of a similar age” (DfE, 2015, p. 102), however Jo thrived within the specialist environment, particularly when accessing creative and physical based activities.

Jo was verbal and had the capacity to engage in a two-way conversation with both peers and adults. Jo could bring new information to a discussion, reflect (with support) on events or experiences and converse with an adult to solve simple problems. Additionally, Jo could be described as an empath: “a person who has an unusually strong ability to feel other people’s emotional or mental states.” (Cambridge University Press, n.d.).

Jo and their family were supported by the local authority under Section 17 of the Children Act (1989) and identified as a “child in need”. Jo’s mum had a history of mental health challenges; eating disorder, anxiety, personality disorder and used recreational drugs, all of which began prior to Jo and their siblings being born. A multi-agency team of social services, educational psychologists, the learning disability team and education worked with the family and specifically with Jo to support their health, education and well-being. The Department for Education (2011) highlights the importance of services working together when SFP is used to support a child to avoid repeating the failings detailed in the second Serious Case Review of the death of Peter Connelly (Department for Education, 2010).

The Practitioner

The practitioner’s professional position and epistemological perspective is as the Outreach and Inclusion lead for a geographical area within mainstream primary schools and a Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) teacher. This was the practitioner’s first experience of using SFP within a classroom setting with an autistic pupil.

Based on educational assessments and professional experience of the pupil for two academic years, the practitioner believed Jo was verbally and cognitively able to co-construct an appropriate reality to engage in SFP as described in studies by De Shazer et al. (2021) indicating that SFP could be suitable for them.

The practitioner was supported by their class team: three teaching assistants who had also worked with Jo and their family for the last two years. They noted potential safeguarding concerns and a safe space for the practitioner to debrief (Brief, 2010).

Professional codes of ethics, as outlined by the European Brief Therapy Association (2021) and the British Educational Research Association (2018) were adhered to.

The Setting

The intervention took place within a primary SEND classroom. The classroom supported 10 primary aged pupils with a range of needs including autism, speech, language and communication needs (SLCN), global development delay (GDD) and severe learning difficulties (SLD).

SEND classrooms are specially adapted learning environments which meet the needs of the individual pupils’ learning styles, sensory regulation, physical abilities and co-occurring challenges to support each pupil achieving their full potential (Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2008).

The practitioner’s teaching approach and classroom environment was based on child-led learning and a continuous provision environment - an approach which allows the pupils to explore, learn and choose their own learning activities which are then observed, scaffolded and facilitated by the practitioners (Bryce-Clegg, 2015). This environment provides ample opportunity for ‘problem-free talk’ in the shape of small world play, drawing, sharing a story or construction and highlights how SFP can parallel “a child’s way of being in the world” (Berg & Steiner, 2003); never analysing problems and instead using trial and error to find their way forward.

Visual Supports

A key element of a specially adapted learning environment is the use of visual supports as a communication tool to express an individual’s wants and needs, improve understanding, to make choices and reduce frustration, and can range from single pictures to short videos (Johnston et al., 2003). They support a person’s expressive and receptive language by circumventing the limitations of verbal communication (American Art Therapy Association, 2017).

Visual depictions have been used throughout history to convey and co-construct meaning, for example through hieroglyphics and cave drawings. Visuals can function as a language because of the meaning that lies within the symbolic form of the image and can therefore be adapted as a means of universal communication. Morell (2011) states that visual depictions “can serve as both a language and as a way to express and explore unsayables”. This is especially true for an autistic person or when exploring abstract concepts.

The Intervention

As a retrospective case study, written informed consent from the pupil and family were not obtained. Pseudonyms have been used for confidentiality and anonymity.

The case study sought to explore if SFP could be utilised within a primary education setting to support the well-being of an autistic pupil when individually adapted to support their communicative needs. The aim was to observe if the autistic pupil could engage with and respond to SFP within an educational environment with a safe and familiar adult.

The aim was explored through three SFP sessions which were predominantly comprised of best hopes, the miracle question and scaling. The interventions will be presented chronologically and reported in the first person as described by the practitioner.

Session 1

My first SFP session with Jo was opportunistic and occurred as I was setting up the classroom for our Friday afternoon activity.

Jo was engaging in an independent activity within the classroom as they had become dysregulated during break time. Jo had chosen to regulate themselves through independent colouring and drawing.

When Jo wanted to open a discourse with me, they would often ask me about my family. On this occasion they asked me if my husband and I ever shouted at each other and if I shouted at my children. We had a conversation about why adults might sometimes shout at each other and at their children and discussed healthy ways to approach this. Jo responded by saying that their mum ‘just shouts all the time, about everything’, that it made them ‘feel sad.’ Jo’s experiences and understanding of a normative homelife was underpinned by their social backdrop and based on an assumption that shouting, as a means of communication, was a key element of ‘family’.

Jo did not specify their best hopes, as in a typical SFP session – this was beyond their independent cognitive ability, however I took this as Jo sharing ‘what brought them here’ (De Shazer et al., 2021). Essentially, I scaffolded Jo’s best hope based on my professional knowledge and experience of them. I feel the co-construction of a best hope in this way requires a holistic and historical understanding of the individual. This can be considered both a limitation and strength of the case study.

Given that ‘hope’ is considered a key factor in therapeutic change (Blundo et al., 2014), I took the opportunity to ask the miracle question basing it on the hope that Jo wanted a calmer household.

The Miracle Question

I was mindful about using the miracle question with Jo, not only given the safeguarding concerns but also with respect to balancing their expectations and not giving false hope (Mulawarman, 2014). There was the potential for Jo, given their autism, of taking the question literally and therefore misinterpreting that the miracle was going to occur, a risk highlighted by Stith et al. (2010).

Jo was a fantastical thinker and often told creative stories to mask adversity. It required greater effort for Jo to process questions and information; it takes considerable cognitive ability to understand and formulate a preferred future; the concept of time, an awareness of others, independent opinions and thoughts (Droit-Volet, 2012). Therefore, in addition to ‘therapeutic pauses’ (De Shazer et al., 2021), at times I either excluded phrases or replaced suggested language with familiar words and terminology that were easier for Jo to process. For example, I did not use ‘strange question’ as suggested in De Shazer’s More than Miracles (2021) because in our specialist setting it would not be considered ‘strange’, moreover, Jo could potentially hyperfocus on that particular word instead of the question itself.

I began by asking Jo if I could ask a question.

Practitioner: Can I ask you a question?

Jo: Nods

Practitioner: I want you to imagine that you go home from school…, you have your tea…, play with your toys… and go to sleep…. When you’re asleep a miracle happens.

Jo: Looks confused…

Pause for processing – practitioner re-phrases

Practitioner: Something magical happens, and when you wake up, no-one is shouting anymore…. How would you know that something magical had happened?

Jo: No-one would be shouting any-more!

As I asked the miracle question, I realised Jo did not understand the word ‘miracle’, after pausing and giving time for processing I rephrased the question. Jo brusquely responded with ‘no-one would be shouting anymore’ which could be interpretated as Jo repeating the question and not a reflection of their understanding, however the tone in which it was delivered alongside their body language implied they were offering a literal response (Vicente et al., 2023).

I acknowledged Jo’s answer and moved forward with the conversation, listening out for their hopes and unfolding reality.

Practitioner: That’s right, what would be happening instead of the shouting?

Jo: Everyone would be happy and laughing!

Practitioner: That sounds lovely. What else?

Jo: Mummy would make me a nice breakfast.

Practitioner: What would you have?

Jo: Hmmm, honey on toast. And coco-pops!

Practitioner: I love coco-pops too! What would happen after that?

Jo: I would get dressed and be ready for the bus.

Practitioner: What would you do after school?

Jo: We would go to the park.

It would be easy to overlook the simplicity of Jo’s responses and strive for a more detailed visualisation. This interaction highlights how my comprehensive knowledge and understanding of Jo is beneficial to the co-construction of their preferred reality as the events they address are of significant importance to them – not only having breakfast at all, but specifically being made their favourite breakfast by mum. The differentiation in the breakfast he receives before school not only reflects the mental state of mum but the outcome of their day, feeling of safety and their ability to remain regulated.

Throughout the miracle question, I made attempts to redirect Jo towards visualising what they would be doing if something magical happened as, at times, Jo’s answers were heavily focused on what their mum or brothers would be doing instead.

Practitioner: After you woke up, what would you be doing if all the shouting had stopped?

Jo: I would play in my room and mummy would come in and give me a big hug then make me breakfast!

Practitioner: Then what would happen?

Jo: She would give me a big wave when I got on the bus for school and make pasta for tea!

Practitioner: Sounds yummy! What else would you do?

Jo: I would play on the green with my brothers and friends.

Jo: Can I go outside to play now?

Practitioner: Of course, you can.

Self-awareness and identity can be complex with autistic people - some have a strong understanding of the self, whilst others remain limited (Huang et al., 2017). Jo’s self-identity and awareness were inherently inter-connected to that of their mum and brothers and challenging for Jo to dissociate from them.

Despite these intricacies, Jo was able to independently visualise, and verbalise, their preferred future, one where they were happier and their home calmer.

Jo clearly indicated the end of our session by precipitously asking to play outside. Jo was presenting as calmer, happier and more relaxed than prior to our conversation and I felt confident that our interaction had a positive impact.

Jo remained positive for the remainder of the school day, and I planned for a scaling session on the following Monday.

Session 2

Scaling – 1

The first scaling session took place on the Monday after the miracle question during a one-to-one session with Jo. This time was part of Jo’s structured daily timetable and set aside for them to work on their individual targets. Jo and I were in a quiet space with no distractions.

We settled into our session with some drawing - Jo’s preferred activity and engaged in some problem free talk. During this time, I noticed Jo was rocking their body more than usual and finding it difficult to focus on the activity. I gave Jo a little more time to draw to support their regulation. After a few more minutes I asked Jo what had been better at home.

Jo: My mums friend stayed over, and we had the best time ever! (Jumping up and down on the seat, hands flapping (stimming))

Practitioner: How exciting! Why was it the best time ever, what did you do?

Jo: We had breakfast at our house then went to the aquarium. We had so much fun, and everyone was happy! (Talking very fast, bouncing and stimming became more intense)

Jo was extremely excited to tell me about their weekend, they were physically animated and ‘stimming’ during the conversation by flapping their hands.

Stimming is a repetitive self-stimulatory behaviour which autistic individuals may exhibit to manage sensory input, stress and anxiety, or for enjoyment (Kapp et al., 2019). Stimming varies and can include body movements such as rocking, hand flapping or involve objects to flick, spin or twirl (McCarty & Brumback, 2021).

I made the decision not to go ahead with the scaling session as Jo was presenting as dysregulated, overwhelmed and processing big emotions. We continued with our usual session to support Jo’s regulation and predictable routine.

Session 3

Scaling – 2

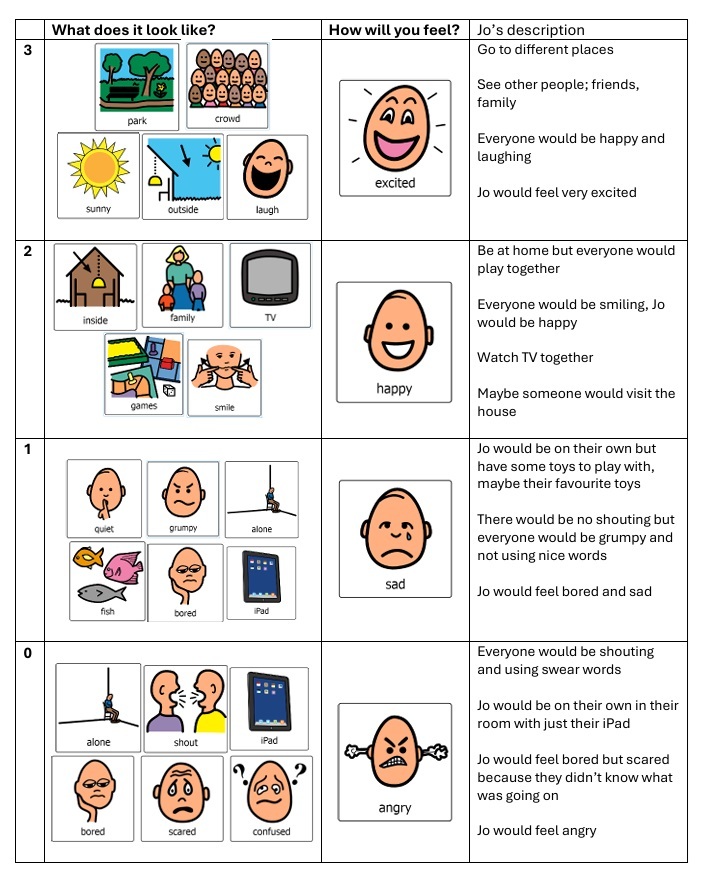

The second scaling session took place the following day, during the same allocated one-to-one session. Jo was notably more regulated which allowed us to complete the miracle scaling (Figure 1).

To support Jo’s communication and processing needs it was necessary for me to adapt the approach using visual supports to scaffold our conversation. Visual supports play an important role within specialist education settings to facilitate pupils’ expressive and receptive language (Johnston et al., 2003) – a visual approach is also recommended in Brief (2019). Co-constructing our conversation in this way enabled us to set small, achievable goals suggested by De Shazer et al. (2021) and clearly identify differences in how things could look and feel for Jo in a flexible but measurable way (Berg & Steiner, 2003).

Figure 1 was created using an online tool during the following conversation. Jo selected the visuals that represented their feelings and experiences, used it to make choices and support the retention of information. Using a scaling of zero to three was appropriate for Jo’s level of understanding and emotional knowledge with three being the day they described in the magical question and zero being the worst.

Practitioner: Number three is your best day, like the one we talked about after something magical happening. Do you remember?

Jo: Yes. I love that day!

Practitioner: And zero is your worst day ever. Like when you told me that everyone was shouting and not being very nice to each other.

Jo: Nods

Practitioner: Shall we look at three or zero first?

Jo: Three.

Practitioner: Brilliant one to start with! What would that look like? …

Jo: (no response, Jo sat looking at me)

Practitioner: What would you be doing?

Jo: Going out to lots and lots of places and seeing lots of people!

Practitioner: Amazing! And how would everyone be feeling?

Jo: Everyone would be happy and smiley and laughing!

Practitioner: And how would you be feeling?

Jo: Super excited!

Practitioner: This really does sound like the best day ever! … Do you want to add in anything else?

Jo: Nope.

Upon reflection Jo’s description was left too general, they could have built a more detailed picture had I encouraged them to develop responses around their feelings and instead persisted with ‘what else?’ questioning as suggested in Brief (2019). Conversely, focussing on feelings connected the action to the emotion making it a real and measurable preferred future for Jo.

We moved on to discuss what ‘zero’ looked like for them then completed ‘one’ and ‘two’. Jo found this a little more challenging .

Practitioner: So, what would be happening in number one, if things were just a tiny bit better?

Jo: … no-one would be shouting.

Practitioner: Ok, what would they be doing instead?

Jo: No answer

Practitioner: … Would everyone be smiling and happy?

Jo: No, they would be grumpy.

There was a distinct change in Jo’s demeanour as the conversation unfolded; their head dropped, they became sullen and began to mumble – they physically and metaphorically retreated into themselves. I prompted with further questions after pausing for thought and processing time, but Jo was disengaging and becoming enveloped within the emotive experience.

Practitioner: … Would you be going out with your mum?

Jo: No.

Practitioner: … Would you be playing with your brothers?

Jo: No, I’d be playing on my own.

Practitioner: What would you be playing with?

Jo: Just some toys … maybe with my fish.

Practitioner: You love playing with the fishes, don’t you?

Jo: Yes (smiles).

I offered choices here as Jo continued to present with early indicators of dysregulation and overwhelm.

Practitioner: Do you want to stop there, or shall we try and fill it in?

Jo: … fill it in.

Practitioner: Ok, let’s do it together. …

This reaction from Jo highlighted the impact that immersion in the experience and the resulting emotions can have during scaling - the exploration of these feelings brought the emotions to the fore. As an empath Jo feels ‘too much’ (Jurkévythz, 2018) and too intensely (Fletcher-Watson & Bird, 2019) therefore future interventions or research should be mindful of post support networks and protocols surrounding the pupil.

Once completed I asked Jo what number they were today.

Practitioner: What number would you be today?

Jo: … maybe a one?

Practitioner: Ok, … What would need to happen to get to number two?

Jo: no answer, becoming frustrated

Practitioner: In number two you said that you would be playing with your brothers? What do you like to play with them?

Jo: We play outside on our bikes and go really, really fast. Like this - zooooom!

Practitioner: Wow! Playing on your bike with your brothers sounds like so much fun! How did you get them to come outside with you?

Jo: I just asked if they wanted to play races on the bikes!

Practitioner: Do they like doing that?

Jo: Yes, it’s their favourite thing.

Practitioner: Do you think they’d like to play that again?

Jo: Yes. I’m going to ask them when I get home today.

When I asked Jo what would need to happen to get to a ‘two’, they became frustrated as they did not understand the question; Insoo Kim Berg might suggest the wrong question had been asked (De Shazer et al., 2021), in this instance the verbal asking of the question did not align with Jo’s communication need. I broke things down further and used the visual scaling to support. Jo had described being ‘number two’ as them and their brothers playing together therefore, I sought out ‘instances’ as suggested in George et al. (1999) asking Jo about times when this had already happened. I scaffolded my questions using ‘Wow and How’ statements which are designed to encourage children to positively reflect on their own lives (Nims, 2007), highlighting to Jo that being at ‘number two’ was and has been a reality for them. Jo lit up as they decided to ask their brothers to play that evening. It felt right to end the session at this point. Firstly, because Jo was in a good place, happy and positive about their plan to move forward and secondly because Jo was presenting with sensory dysregulation due to the excitement they were feeling about playing out that evening.

It would be beneficial to continue scaling with Jo and extend it by focussing on ‘chunks’ of areas important to them: Jo and mum, Jo and their brothers, just Jo (McKergow, 2016) allowing them to see that although everything is connected things can move separately.

Discussion

This retrospective case study sought to explore if SFP could be utilised within a primary education setting to support the well-being of an autistic pupil when individually adapted to support their communication style through observation of engagement, pupil response and practitioner reflection. The study found that through a holistic understanding of the pupil coupled with appropriately modified communication according to individual need, an adapted SFP approach could be utilised within a primary education setting to support an autistic pupil’s well-being.

Reflecting on the intervention and my input as the practitioner I believe using the approach was successful from two viewpoints; firstly, the use of visuals as a means of communication to support the co-construction of Jo’s preferred future and secondly, Jo left the sessions they were able to engage with looking notably happier, calmer and more positive about home. Whilst this may not appear to be immediately substantial, for Jo it was a “small but meaningful change” (Connie & Froerer, 2023, p. 261) which had the potential to lead to more significant and permanent changes.

In a longer study, a wider range of success criteria could be examined, such as a reduction in conflict at home, improved relationships with peers and educational achievement, but for Jo, and within this retrospective and time limited case study, aiming for being regulated enough to engage with and respond to SFP within an educational environment was an effective measure of success.

The intervention took place within a specialist education setting whereby the pupil had daily, structured one-to-one time with the class teacher. Although this may not be the case for all pupils within specialist settings, this was necessary for Jo. Had this intervention been delivered in a mainstream setting without the one-to-one element, it is questionable whether the intervention could have been delivered at all.

The case study also highlighted that when using SFP with neurodiverse pupils, it is perhaps better to have an established relationship; knowledge of their history and communication style; not only to facilitate a scaffolded approach but to identify nuanced signs of dysregulation, offering choices when needed to reduce overwhelm, when to stop a session and most importantly to safeguard the pupil.

Overall, I believe the success of this retrospective case study was at least partly because it was delivered by a familiar and safe practitioner to the pupil. However, I question how much my relationship with Jo and associated assumptions hindered my exploration of their preferred future given my understanding of their home and history. External validity and rigorous protocols could potentially mitigate practitioner and pupil relationship to some extent.

Conclusion

Utilising SFP with autistic pupils within primary school settings on a one-to-one basis, rather than within a group or family context, is relatively unexplored.

This case study examined its use within a safe, structured and familiar environment for both the practitioner and pupil, encompassed by hierarchical academic and pastoral support systems to ensure the safeguarding of both the pupil and practitioner.

The use of SFP with autistic pupils within their educational setting could impact not only their well-being but also their ability to access their education and reach their potential in other areas of their lives through establishing transferable skills, building up their self-identity, resilience, and sense of belonging. Furthermore, the findings could have important implications for educational practice and SEND support, however more research is needed. Future studies should explore the long-term impact and outcomes of the use of SFP with autistic pupils and additionally investigate the educational environment and unique elements of the intervention, with a particular focus on the relationship with practitioner, support and structure within the setting.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest.